Saturday, January 01, 2005

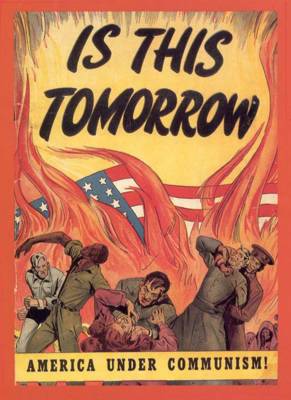

One dictionary defines the phrase 'red herring' as something that draws attention away from the central issue, and tells us that the origin of this expression is the practice of dragging a smoked herring along a track so as to throw off tracking dogs. The fear of the spread of 'Communism' acted as one such red herring during the McCarthy era in the US : instead of asking crucial questions such as what 'communism' was, and what its historical origins, socio-economic principles, and vision of human destiny were (which was the 'central issue'), the US administration tried to rouse the hysteria of the people against the Reds. It is arguable that in the late 1990s, the term Toleration has become the red herring for us with respect to various issues : rather than asking what these issues are really about, to what extent the claims associated with them are in/valid, how people whose lives are directly affected by them view them, and what inter-connected configurations of socio-economic-cultural questions these issues raise in their wake, we often behave as lazy school-children and try to wash our hands off such difficult home-work under the illusion that our laziness is justified by appealing to (an ill-defined) Tolerance.

Since, as an Old Master said, the beginning of wisdom lies in the definition of terms, I shall make one attempt towards 'wisdom' by first defining Toleration. I shall call a certain person to be tolerant of a belief or practice if she : (a) recognises that it is genuinely different from beliefs and practices located in her own world-view, (b) disagrees with the former, (c) and yet provides some space for the former to develop. Let us now apply this definition to two examples.

(1) To be 'tolerant' of Islam, it will not therefore do to go around entertaining vague notions of what Muslims believe and practice; nor can one say that the mere act of sharing a meal, watching a film, going to the same university, or playing a football match with a Muslim in itself amounts to 'toleration' (it goes without saying that the latter activities are most welcome, but they do not constitute toleration as I understand the term here). A person, David, can be said to be tolerant of a Muslim only when he first undertakes a careful study of the principles of Islam and develops some acquaintance with believers who practise these, and thereby comes to know what the precise differences are between his world-view and the life form called Islam. It may happen that in the process David realises that he and his Muslim acquaintance are living in two worlds separated by a wide chasm over several issues, and this will lead both of them to (re-)examine the validity of the claims that are raised in each other's world-views. In spite of these (possible) crucial differences, David must be willing to make some space, socially, culturally and legally, so as to ensure that the Muslim is able to live and flourish in the latter's religious world.

(2) To take an example from the other end of the spectrum, another person, Imran, can be said to be 'tolerant' of an atheist only when he is patient enough to know what the atheist really believes in (or disbelieves in), and how she lives in accordance with these dis/beliefs. To (apparently) live in harmony with an atheist, greeting her with a polite smile every morning, having coffee with her at the mid-day break, and going to the movies with her every weekend, while believing inwardly that she is morally corrupt or eternally damned, is not toleration but paternalism. To be truly tolerant of each other, both of them must engage themselves in a mutual process of (re-)examining the truth-claims that they respectively make within the horizons of their own worlds, and ask each other the hard, unsettling, and difficult questions that go with such (re-)examinations. To claim that they are 'tolerating' each other without having engaged in such investigations would be a parody of that term; this is but a thin and fragile 'tolerance' which can be used a mask for disguising the deep hatred and mutual distrust that may lie within. Finally, after such mutual inquiries, Imran must be willing to allow his atheist friend some conceptual and social space wherein she can develop her atheist convictions and live in accordance with them.

What have we observed in the above analysis? Firstly, the notion of tolerating someone must be carefully distinguished from the attitude that goes by the slogan : 'I do my thing, and you do your thing. Let us not disturb each other'. This slogan refers to a static state of affairs, a stalemate or a standoff between two parties, whereas toleration refers to an ongoing process, a never-ending dialogue between them. If I, who am religious, am to truly tolerate an atheist friend, it means that (a) I believe that she is mistaken in holding some of her beliefs, (b) wish, nevertheless, to engage her in a continuous dialogue over these beliefs, (c) and yet am willing to allow her space to develop her views. Toleration, as I understand the term, is therefore not a passive state but an active response, a desire to learn more about the other, and this is the reason why (b) is important. I am said to truly tolerate members of communities to which I do not belong only when I simultaneouly affirm (a), (b), and (c). To accept (b) and (c) without (a) would mean that I am shying away from the hard home-work of analysing truth-claims, to accept (a) and (c) without (b) would mean that I am hiding my lack of desire to know the other under the cloak of 'toleration', and finally to accept (a) and (b) without (c) would mean that I view the others as a constant threat at my horizons and cannot coexist with their otherness.

In short, I understand 'toleration' and 'dia-logue' as co-terminous, which is to say that I truly tolerate only those people with whom I am engaged in a constant dialogue. For example, I cannot be said, strictly speaking, to tolerate Tibetan Buddhists, anti-abortionists, Japanese Shintoists, or Chinese communists. The reason for this is not because I wish to exterminate them or cast them into cold dungeons (I do not) but because I do not know anyone belonging to any of the above communities, and, therefore, cannot obviously enter into a living dia-logue with them. I can, of course, still say that I tolerate Tibetan Buddhists but this 'toleration' would only be in a trivial and formally empty sense. On the other hand, I can say that I tolerate Anglican Christians, Marxists, Buddhists, agnostics, and atheists because not only do I know some Anglican, Marxist, Buddhists, agnostic, and atheist friends but also because I am engaged, every now and then, in a mutual process of discussing their views with mine.

Indeed, the slogan, 'I do my own thing, you do yours', far from being a manifestation of 'tolerance' can be used to mask pernicious forms of seething underlying hatred. In saying this, I do not imply that we must jump to the other extreme slogan which goes as, 'I know it better than you do', and which tries to legitimise all sorts of 'interventionist' activity. All of this brings out the dire need of (c); we must be willing, in spite of our mutual differences, some of which can be radical, to engage ourselves in the never-ending process of (re-)negotiating and (re-)establishing the social and cultural boundaries which mark off certain zones as belonging to 'us' and 'them'. This process can be given the shorthand term 'toleration'.

Friday, December 31, 2004

Now is the Time

Sometimes your ability to clearly express your thoughts is limited by the vocabulary of the linguistic world that you inhabit. In English, for example, this is especially the case when it comes to temporal expressions since we have to make do with only one word 'time'. Greek, for example, on the other hand, has two words chronos and kairos. Chronos corresponds quite closely to our day to day notion of time, that is, of time as sequential, numerical, and chronological. It is this time that we measure with a clock (or a 'chronometer'), and is orderly and predictable. Therefore, according to this understanding of time, today's date is January 1.

Kairos, on the other hand, cannot quite be translated into English with a single word, but refers to a period of time when something special or unique happens : it is the right moment, the critical stage, or the opportune time. Kairos time is that which marks out a period of disruption in the normal flow of events, a time when the ground is shifting, and the old habits and beliefs are undergoing a change. In this sense, we think of January 1 (otherwise just a point or a dot on the calendar) as a 'new way', or a 'new opening'.

In our bygone days of youth, we used to have magnificent dreams, dreams that we would soon dispel the darkness from the farthest reaches of the planet, and make the world a happy place for everyone to live in. Today, in our senescence, we instead find ourselves sitting by the fire nodding our heads as we sigh over our heroic but failed attempts. We have been overtaken by fresh blood which lampoons our efforts alleging that we were simply trying to mask our sinister intentions behind grandiloquent slogans. Some of them continue to live uneasily among the broken-down relics of our massive structures, some pick-and-mix fragments from these relics in order to build their own imposing monuments and often deliberately hide their indebtness to us, and some lament that all building activity must now be given up as pointless. Meanwhile, the writing on the wall (that is, whatever is left of the Wall, in Berlin or elsewhere) is clear : All conversion activity is a form of intolerance. Thank you very much, we don't need any more missionaries after the mess that you have made of this lovely, green world of ours. Just leave us alone, will you?

'We' therefore stand accused at the altar of the Goddess (or, God?) called Tolerance. As counsel for the defence in this post, I plead guilty to the crime of often having used dishonest, disreputable, atrocious and violent means in our desire to convert. I willingly and sincerely accept the corrective punishment in some 'penitentiary centre' of having to rethink over what went wrong that led us to resort to violent means in our desire to reach out to the others. However, I also state in the same breath that we must most carefully and resolutely separate (a) the desire to convert others from (b) the tools or methods that are used to express this desire. Indeed, I shall argue more than this : it is possible that even our accusers who now sit smugly on the benches out there, smiling cynically at us, have not completely given up (a), they have only changed the nature of (b) that they use.

The desire to bring others around to our point of view is a very common human desire, though there are significant differences among human beings as to the extent to which they may have this desire. I shall refer to people who have this desire, to a greater or lesser extent, as Evangelists. More specifically, I shall define an Evangelist as a person who (E1) believes that she has a certain message to offer to the world which she thinks is currently engaging in behaviour that is terribly dangerous, or holding beliefs which are highly misguided, and (E2) hopes that the world will come around from its current state of affairs by accepting her message and undergoing a process of reformation. Different Evangelists will, however, express (E1) and (E2) in divergent ways : for some, all human beings must hear this message, for others, it is sufficient that only a few come to hear/accept it; again, for some, it is most urgent that this message is heard by everyone immediately, for others, it may be reasonable to expect that it will take a few generations before it becomes widely-known; for some, it is necessary that the others, after hearing the message, actually undergo a metanoia and cross, once and for all, the threshold that clearly separates the old life from the new, for others, it may be enough to have sown some seeds of doubt in the minds and hearts of the hearers.

Let me explain these differences by contrasting a woman's (possible) relationship to feminist theory with my personal liking for Beethoven's symphony No 9. A feminist is, roughly speaking, a woman who believes that all women who inhabit religious world-views have their lives greviously damaged since such englobing perspectives are rooted in patriarchal assumptions. As for my like of that symphony of Beethoven, I believe that listening to it would be a good experience for other people, if they had the means and the time to do so. Therefore, both a feminist and I are Evangelists, but now note the differences between us. Firstly, the feminist would like to ensure that everyone (that is, every man and every woman) in this world comes to hear about her analysis of the patriarchal foundations of human society; as for myself, I would admit only too readily that for a beggar it is infinitely more important to save money to buy a loaf of bread than to listen to that symphony. That is, the feminist's Evangelism is universal in a sense that mine is not. Secondly, for the feminist it is extremely important that every human being comes to know about her analyses as soon as possible (and, even better, accepts them too), whereas I really couldn't care how many more years it takes before everyone on this planet listens to that Beethoven symphony.

Indeed, it is may be the case that there is something of an Evangelist slumbering deep even within those of us who may otherwise claim not to have any such evangelical intentions. To be sure, we may not quite have the sense of urgency that (many) feminists do, but in our daily interactions with our friends and relatives, and in the processes of telling them what is right and what is not, what we like and what we do not, what we would want them to like and what we would not, we may be living, unbeknownst to ourselves, very much as Evangelists. On the basis of this discussion, then, let us ask : is every attempt at conversion, or, to use my terms, at Evangelism (in the sense (a) above) necessarily ruled out by a vague appeal to the divinity of Tolerance? If we reply in the affirmative, it would imply that we must ban all feminist literature, as well prohibit the (the thousands of) subtle and express attempts at Evangelism that we make on a daily basis with those who live with and around us. Hold on tight, for here is more trouble to come.

(1) There are anti-smoking Evangelists all over the United Kingdom who wish to have smoking banned in public places. That is, they believe that something is terribly wrong with a world where smoking is allowed in public spaces (E1), and they campaign for a different world where people will come to see the terrible mess that they have made by allowing such smoking, and will repent and change their laws (E2).

(2) Marxist theorists have regularly pointed out how religious systems are embedded within inegalitarian structures, and how the latter have entrenched themselves even more firmly by making use of legitimising doctrines provided to them by the former. They believe that currently a large proportion of human beings lives within oppressive systems (E1), and would wish to bring it about that these latter are dismantled and more 'transparent' ones are established in their place (E2).

(3) Parents are Evangelists too, and if Evangelism is to be forbidden, so too must parenthood for parents wish to bring up their children according to a specific set of norms and values. For example, if you are born into an orthodox Jewish family, you shall be brought up as a Jew (and be taught that 'being Jewish' is a live option for you in a sense that 'being Marxist' is not); and exactly a similar pattern of argument applies irrespective of whether the family you are born into is Muslim, Hindu, Christian, Taoist, Sikh, Confucian, neo-Pagan, Shinto, Theosophist, Anthroposophist, Buddhist, Jaina and so on. An atheist couple may like to self-congratulate themselves with the belief that they have escaped the conceptual net of this argument; as a matter of fact, however, they have not. It is very likely that an atheist couple will bring up their children to be atheists, and would be, I strongly suspect, mortally grieved to learn that one of their children has become, say, a Muslim. Whether explicitly or implicitly, parents believe that there are certain aspects of the world 'out there' that are nasty, bad, brutish, and dangerous (E1), and they either wish to (actively) change those aspects so that the world becomes a 'better place' for their children to live in, or, at least, (passively) to keep their children away from them (E2). It is impossible to avoid the conclusion that every type of education (whether it is religious, secular, liberal, post-liberal, feminist, post-feminist, atheistic, agnostic, Marxist, critical Marxist, and so on) is, at some level or the other, a form of Evangelism, whether this is kept disguised or made explicit. Therefore, to rule that (a), the desire to convert others, must be declared illegal is tantamount to saying that all schools and universities must be razed to the ground.

(4) There are some thinkers in the 'Western' world, usually (though not necessarily) from an atheist background, who claim that in discussing crucial ('public'/'scientific') issues such as abortion, euthanasia, capital punishment, and stem-cell research, people should not make appeals to ('private'/'traditional') religious sources. Therefore, such thinkers believe that there is something very wrong with a world where such appeals are made (E1), and claim that we should strive to establish a new world where these appeals are declared to be illegal (E2). Consequently, such atheism too is a form of Evangelism, this time an Evangelism which believes that things would work out better for everyone if it were possible to remove voices stemming from a religious context from the 'naked public square'.

(5) The contemporary nation-state itself engages in an active 'mission' of Evangelisation in order to spread its secular nationalism through a process in which older religious-sounding terms are 'translated', wherever possible, into their secularised versions. For example, martyrdom is redefined as death in a war waged by the nation-state, blasphemy is now rather to be understood as treason against it, and the notion of worship is reconceptualised as the ultimate loyalty to it, a loyalty that is to be expressed through national anthems, commemoration ceremonies, and the retelling of the lives of its historical founders.

In short, if we say that (a), namely, the desire to convert others, must be rooted out and branded a form of intolerance, all feminist literature must at once be consigned to the flames, all anti-smoking Evangelists imprisoned, Marxist theorists driven underground, parenthood abolished, the views of (militant) atheists proscribed, and the very existence of the nation-state declared illegitimate. Would that not simply become yet another example of how some of the greatest types of intolerance in human history have been sanctioned in the 'name of Tolerance'?

Let us now take up what I shall call the 'litmus-test' of anti-Evangelism : Is postmodernism, and particularly the version of it that (apparently) sets its face against all activities of conversion as being 'imperialistic', 'paternalistic' and 'totalitarian', itself a kind of Evangelism? To be such a postmodernist you must (a) believe that there is something grievously wrong with the world 'out there' where believers in some meta-narrative or the other such as Muslims, Christians, Buddhists, Marxists, atheists, 'scientists' and so on are trying their best to convert one another, and (b) either have a mild occasional wish that the world was not such, or have a stronger desire to somehow (though you-know-not-how) bring it about that such conversion activity came to an immediate halt. Now in terms of my definition above, (a) here corresponds to E1, and (b) to E2, which is to say that this version of postmodernism too is a form of Evangelism. In fact, the only absolutely consistent non-Evangelical postmodernist would be a person who withdraws to the silence-wrapped heights of the Himalayas straight-away and never utters, ever again, a single word for the remainder of her life. Anything that she might say thereafter (either as an affirmation or as a denial; or as a denial of either of these alternatives; or as a denial of a denial of .....) will be taken as evidence, against her alleged non-Evangelism, in a court of law.

Why is it the case, then, that some world-views seem to be more Evangelical than others? For example, it is more common to come across a Christian, a secular nationalist, or a Marxist Evangelist than, say a Hindu or a Jaina one (or, at least, this was the case until very recently). The reason for this is that Evangelism belongs to the 'intrinsic core' of beliefs of certain world-views, while in others it may be an optional extra that lies at the periphery. For example, if you believe that human beings have only one life-time in which to undergo a decisive change from the present empirical conditions of finitude to an infinitely better state to be established in the future, you are more likely to exhibit greater Evangelical zeal than someone who believes that this perfection can be attained over several life-times. Therefore, as a Marxist it might be imperative for you to go out into the world straight-away and try to make Marxists out of everyone; as a Hindu, on the other hand, you could sit at home and actively hope that those who are, say, Jews and atheists in this birth will, during and over a period of future world-orders, come to be born into a Hindu family, and thereby proceed towards final liberation. This, incidentally, is not to claim that Hinduism is more 'tolerant' than Marxism, for the basic issue in this context is the validity of the truth-claims that are being raised within the Marxist and the Hindu horizons respectively. If a Marxist can provide sufficient reason why a Hindu should not have epistemic confidence in the doctrine of karma and reincarnation, this Evangelical act on the part of the Marxist should rather be viewed as being truly 'tolerant', for this is the act of bringing the Hindu out of her former ignorance to the truth of the matter concerning this doctrine.

In a similar fashion, a Buddhist who believes that the route to liberation from this world of suffering is through the four Noble Truths, which apply to all sentient beings, is likely to display greater Evangelical fervour than someone who thinks that there is, in fact, no such route, or someone who believes, for whatever reasons, that this liberation is possible through alcoholism, or someone who claims that even if one knows about such a route, one should not reveal it to one's neighbours. Again, an atheist who believes that she has a 'duty towards humankind' to expose the illusions that religious believers suffer from will tend to have more Evangelical zest than an atheist who believes that religious folk are in any case incorrigible and should be left to their own devices.

In short, different Evangelists display varying levels of Evangelical enthusiasm, and this is partly related to the differences among the world-views that they inhabit. Let us now move on to (b), that is, the question of the variety of tools that people use (and have used) to express their desire to convert others to their view-point, and it is actually here that most of the trouble starts brewing.

Historically speaking, it is true that Evangelists of a religious persuasion have often used force and compulsion to bring people over to their world-views. Muslims and Christians, in particular, have received quite a bad press in this matter and it is this historical record that rouses the strong passions of many people whenever they come across the phrase 'religious conversion' (which is a more specific case of what I have termed Evangelism and which includes 'conversion to atheism' too). However, in order that we do not commit the fallacy of mistaking what is contingent for what is necessary, we must be patient and willing to (a) find out if there really is a logically necessary connection between the desire for conversion and the use of disreputable and violent tools in that specific religion, and (b) to read what inhabitants of that religion have themselves said about those specific historical instances where violent tools may have been used. To take the case of Christianity, for example, a careful study of its doctrinal history will reveal, firstly, that there is no such connection, and secondly, that many Christians themselves have come to recognise that certain activities that earlier went under the label of 'conversion' were, in fact, betrayals of the Gospel. There is, in other words, no reason to believe that all religious conversion necessarily goes with violent means; much of conversion activity is carried out today through the means of persuasion, discussion, presentation of one's views, and dialogue with others. Indeed, if anything, it is the opposite impression that may be need to corrected in some contexts; that is, we may need to be re-assured that in spite of all the Hitlers and the Stalins of the world, the desire to convert other people to (some kind of) an atheist world-view need not necessarily be expressed through deceitful and violent tools.

Let us take one specific example from the Indian context. The question is sometimes raised, especially in political and legal circles, as to whether or not (Indian) Muslims and Christians should be given the right to convert non-Muslims and non-Christians (and this question acts as a sure red flag to the bulls of historical research who routinely point out instances of Muslim/Christian 'intolerance'). To rephrase the question in my terms, should Indian Muslims and Indian Christians be given the right to Evangelise?, and in order to show why they should be given this right, I shall point out some of the implications of declaring Evangelisation to be illegal.

(1) Let us say that a certain group declares that such Evangelisation is illegal. This group would then have to make at least one claim, X such that X : Muslims and Christians should not be allowed to Evangelise. Now X can be further 'broken down' into X1 : There is something very wrong about living in a world where Muslims and Christians have this right (which corresponds to E1), and X2 : We must do something to bring it about that they do not enjoy this right in the future (and this corresponds to E2). Therefore, those who put forward X are themselves, according to my terms, Evangelists, and having put forward this claim X, members of this group would themselves have to first Evangelise others over to their view, X. That is, if I happen to be neither Muslim nor Christian and yet refuse to accept X (for example, I could be a militant atheist in Bangalore or a Marxist in Kolkata who is aware that my right to Evangelise others to my atheism or my Marxism may be taken away, by subsequent extension of X), this group will first have to Evangelise me, either through persuasion or physical threats , so that I come to accept X. Therefore, the very act of declaring Evangelisation to be illegal presupposes that Evangelisation is not, in fact, illegal! One way out of this tangle is, of course, to make a difference between 'two types of Evangelisation' by putting forward the claim Y, such that Y : Only non-Muslims and non-Christians should be allowed to Evangelise one another. Even in this case, however, one would still need to Evangelise, only that this time it will be the Muslims and the Christians who would not readily accept Y and who will, therefore, have to be evangelised! Once again, then, the proclaimed illegality of Evangelism at one (lower?) level would be presupposed by its assumed legality at another (higher?) level.

(2) It is possible that the group that makes the claim X is from some kind of a 'Hindu' background (though the question of how justified the group would be in identifying itself as 'Hindu' is a different matter). Suppose, however, that there is another group, members of which call themselves Indian 'secularists' and who make the same claim X : a similar argument to the one above could then be made against this latter group too. It can be argued that these people too have their own brand of Evangelism, an Evangelism to spread 'secularism' (ES) throughout the length and the breadth of the country. Therefore, if Muslims and Christians are not be allowed their own Evangelisms (EM, EC) it must first be pointed out precisely what it is about these latter Evangelisms that cannot be accomodated within the broader framework of a 'secular' state. It may be replied that EM and EC make 'absolute truth-claims', and such claims cannot be permissible since they threaten to tear apart its secular fabric. Possibly so, but we must also keep in mind that ES itself goes with an absolute truth-claim A, such that A : It is an absolute truth that given the socio-cultural context of India, only that secularism that 'respects all religions' and makes no discrimination among citizens on the basis of their religious background can be accepted. I do not deny, of course, that there are people who would reject A, but it is a fact that most people who do accept A accept it as an 'absolute' non-negotiable claim. If that be so, one would need to show specifically what it is about the 'absolute' claims of Islam and Christianity that immediately disqualifies them from being raised within the horizons of the 'secular' nation. Moreover, Marxist and feminist theory can be easily 'translated', though, of course, in very different ways, into sets of absolute truth-claims too; therefore, unless Indian Marxists and Indian feminists qua Marxists and feminists are to be banned from 'public life', there is not much plausibility for prohibiting EM and EC on the mere grounds that these latter come packaged with 'absolute' claims.

(3) One aspect of Indian secularism is that the nation-state shall 'respect' all religions, and it can be argued that in order to respect a certain world-view the very least that one must do is not to actually hinder those who inhabit it from carrying out certain practices that directly follow from its 'innermost core' of beliefs. To take the case of Christianity, one belief that belongs to this core is that God's love for humanity has been revealed through the Crucifixion-and-Resurrection of Jesus Christ, and that those who have accepted, in faith, this Good News should spread it to their friends and neighbours. Therefore, a Christian could argue that she wishes to deliver this News to those around her, and claim that she would not be able to identify herself as Christian in a nation-state where she is forbidden to do so. That is, Indian secularism can be said to 'respect' Christianity only when it allows EC, for EC is not an 'optional extra' but belongs to the very heart of the Christian scheme of things (and similar arguments apply for EM, and, as I have pointed out above, for (Indian) Marxism and feminism too).

(4) Let us say that someone wishes to remain within the context of Indian secularism (as defined above) and yet denies (the validity of) EC and EM. This could be for various reasons : it may be so that the person has a vague sense of uneasiness with any world-view that makes 'absolute' claims, or may be she objects to certain beliefs and practices within the Christian or Muslim world-views, or perhaps she believes that all religious belief is a pernicious error, and so on. This is a very different type of argument as compared to the ones that we have examined in (1) - (3). The issues that we were discussing earlier were centred around the question of whether any Evangelisation is to be allowed within the socio-political contours of the Indian nation-state, and we came to the conclusion that the declaration that all Evangelisation is, in principle, illegal would subvert itself (for this declaration itself would then be a masked form of Evangelisation). This time, however, we come to the more exciting, and also infinitely more difficult, question of which type of Evangelisation is the correct one : is it the Evangelisation activities carried out by the (Indian) Marxists, the secularists, the Christians, the Muslims, the (militant) atheists, the feminists, the Hindus, or the Buddhists? Here we must be careful not to confuse two logically very different forms of parity : legal parity and epistemic parity. By the former, I mean that all the above-mentioned world-views, and consequently the forms of Evangelisations associated with them, enjoy equal legal sanction from the nation-state. However, it is not for the nation-state to declare that inhabitants of one specific world-view should also regard all other world-views as being on epistemic par with one another. For example, an Indian Muslim may come to the conclusion, (possibly) through a study of Islam and discussions with, say, Hindus, Marxists, and Christians, that Islam is for her a doxastic practice that places within a comprehensive conceptual structure every facet of her existence in a manner that Hinduism, Marxism and Christianity are incapable of doing. And, of course, the (Indian) Hindu, the Marxist, and the Christian can all come to their own respective conclusions about why their specific world-view, and the consequent Evangelisation, is such a 'comprehensive conceptual structure' for them. It is crucial to note here that there is nothing intrinsic to the notion of 'Indian secularism' that can make such declarations invalid. That is, though (Indian) Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and Marxists are all given equal legal sanction to practise their Evangelisations, people belonging to any one of these forms of life cannot be compelled to declare that their own and those of others around them enjoy epistemic parity as well. An Indian Marxist can continue to make --- at the epistemic level --- the 'absolute' claim that all religious belief is a dangerous illusion, while allowing --- at the legal level --- others around her to practise their own Evangelisations, whether or not these latter are religious, atheist, or agnostic. There is nothing 'intolerant' about this; ironically, it is the refusal to patiently listen to the Marxist and to take her truth-claim seriously by making invocations to the elusive authority of Tolerance that should be regarded as a form of intolerance.

(5) Finally, a tricky case from the long and turbulent history of the Christian Evangelical enterprise in India : Christian Evangelists are often accused of making 'converts' out of Hindus and Muslims by promising them financial incentives. Let us examine the issue from four different stand-points :

(a) One Christian Evangelist could put forward the following argument : "If I were to see a hungry man on the street and I had some money in my pocket, I could not care less what religion he puts down as his own on the census form. I shall immediately see in him 'Christ, hungry and naked', and I shall try to help him. This help can be of two types. One is, of course, the immediate one of giving him some food to eat. The other is the more enduring one of trying to find some job that he can take up, and thereby earn some money for his needs. Now it may so happen that after some time, this man on the street becomes curious to know what exactly it is about my set of beliefs that led me to help him on that day; and then I shall introduce him to the Good News of Christianity. To carry on, he may actually accept, in faith, this News and be baptised into the community, or he may not. If, however, he does receive baptism, he has done this out of his own free choice; there is not the slightest element of compulsion involved in the process. What you might now argue is that when I helped that man on the street that day I did this with the hope that he would finally become a Christian someday. I do not, in fact, deny that this is the case, but I ask you to tell me what precisely is wrong with having such a hope. Unless you can give me reasons to believe that the following truth-claim X is invalid, where X : Christ, our Lord, died for us, and He wishes us to turn to Him, I do not see why I should abandon the hope that others around me will, in fact, go to Him when I tell them about Him."

(b) Another Christian Evangelist, possibly a variety that goes under the label 'Franciscan', could pick up the argument from there and chirp in : "You are probably making a distinction between, roughly speaking, 'spirituality' and 'economics' which leads you to believe that the latter has nothing to do with the former. As a matter of fact, however, the way in which I understand my Christianity asks me to believe that no such separation is possible, so that when I feed and clothe a hungry beggar on the street this act is very much a part of my 'spirituality'. Therefore, when you (implicitly) demand that I talk about God only within the churches and not help those on the streets, you are effectively demanding that I stop being Christian. This demand, however, would go against the very foundations of your 'Indian secularism'."

(c) A third Christian Evangelist now comes in : "You are possibly arguing that any act of helping the beggar must be prohibited if this act can be shown to flow from certain (background) motives. In my case, the 'motive' is that I wish to obey the commandment to help the beggar, a commandment which was (derivatively) given to me by my Lord, Jesus Christ, when he (ultimately) ordered us to love our neighbours. In that case, however, neither would a Hindu, a Buddhist, a Muslim, an atheist, or a Marxist, be allowed to help a beggar since in each of these cases the act would flow from some motive or the other. Even if an Indian claims to have no 'world-view' whatsoever and yet helps the beggar, she would still be acting out of a certain 'motive' which in her case would be : I am motivated to help this beggar by my belief that it is a good thing to do so. Therefore, if you want to claim that the mere existence of a motive is sufficient reason to forbid the act of helping a beggar, you shall have to be more specific and now say that no such act is to be allowed only if this follows from a specifically Christian motive. This move, however, cannot be made unless you can show what is so disreputable about this motive that it must be declared to be illegitimate within the horizons of 'Indian secularism'."

(d) A fourth Christian Evangelist may wish to conclude this discussion with these remarks : "A lot depends on how that term 'incentive' is understood. Some of us in the past may have put forward financial gains to Hindus and Muslims with the hope that this promise will necessarily activate faith in the Gospel in them. They were certainly wrong in this matter of using deceitful means for a living faith in the reality of God can only come as a divine gift; it cannot be earned or bought through any human tools. However, some of us have often invited Hindus and Muslims to be a part of our community and share in our liturgical practices of worshipping God whose love for us was revealed through the Son, Jesus Christ. They have become our truly intimate neighbours, and we are commanded by our Lord to love them, and surely, one aspect of loving them involves helping them with their financial needs. Unless you wish to claim that it is wrong to offer financial help to your own close friends, you cannot demand that we stop doing the same and not help these new friends of ours if they may have such needs. This is not to say, as you falsely believe or wrongly suspect, that we give them money in order that they may become our friends; rather, it is because they have (already) been made our friends-in-Christ, and not solely by us but ultimately by Christ Himself, that we wish to give them monetary help (and, for that matter, any other help that we are capable of). By misjudging the nature of cause-and-effect involved in this process, you wrongly think that the alleged 'incentive' comes before a person becomes a member of our community, whereas, in truth, it comes after."

Let me summarise : (1) The prosecution has not made its case that the desire to convert must be made illegal, not least because the people who argue for this move are themselves trying to convert others (either through 'rational persuasion' or by 'legal force') to their view! (2) The (legitimate) demand that violent methods be given up in converting others must not be confused with the claim that the desire to convert others is itself illegitimate. (3) Nor must it be thought that Evangelism is always connected with the propagation of 'religious belief'; not to mention the (non-religious) feminist and the militant atheist, almost every kind of a (possibly non-religious) postmodernist is also an Evangelist. Therefore, if we still wish to hold on to the notion that Evangelism (or 'conversion') is a form of intolerance, we must be willing to accept that this intolerance applies to militant atheism and (almost every version of) postmodernism too. (4) To claim that members of certain traditions such as Islam (or, for that matter, Marxism) have used, in the past, violent means to propagate their views may be very good history. However, to jump (or, even more strongly, to argue that this jump is logically necessitated) from this sound historical observation to the unwarranted conclusion that all the truth-claims made within Islam (or Marxism) are thereby falsified at one stroke is but a manifestation of slipshod thinking. Just as Newton's 'law of universal gravitation' is not falsified by the mere fact that a tyrant of a school teacher beats his students for forgetting it, so too the question of the validity of the claims made within a world-view and the historical record of how these claims were propagated are two issues that are, and must be kept, conceptually distinct.

Thursday, December 30, 2004

The Forgotten Darkness

Now that the long winter nights become brighter than ever with halogen lights, here are eighteen of my songs for the Forgotten Darkness :

(1)

What does one beggar do

when another beggar comes to him

asking for money?

perhaps this is a meaningless question

or perhaps such things happen only in the movies

but as for my beggar

well, he can't do nothing at all

but stare into the eyes of his friend

while above both of them

the despicable winter sun

gently sinks into their tired eyes.

(2)

At the water's edge the beggar

sings the same song a million times

sometimes it is good

to hear your own voice

every noon the kite flies

round and round and round

screaming out her heart

for a fragile peace

that was never hers.

(3)

In this world

there are but three sorrows

one that is real

one that is unreal

and one that lies sleeping

in the abyss of your dark eyes

unknown even to you.

(4)

New year's Eve

the old beggar makes a fire

out of old lottery tickets

and on New year's Day

she changes the old water

in the vase with plastic flowers.

(5)

Christmas evening

The young man gives the beggar

His empty unused wallet.

(6)

Handing him a ten pound note

The girl asks the beggar

To give nine pounds back to her.

(7)

The old dog looks into the beggar’s bowl

And wonders which

Of the ten coins are for him.

(8)

The beggar has fifteen coins

He needs just one more

To teach his dog

How to play Chinese checkers.

(9)

Winter morning

At the temple

A long row of devotees

The beggar too takes out his three coins

And places them in a long row.

(10)

Busy market-square

The beggar and his violin

He is not very good at Mozart

But in this world

At least his dog has ears.

(11)

They say that the old temple

has now run out of priests

and I used to think

that there will be priests

as long as there are beggars.

(12)

Sunday afternoon

The beggar and his dog go fishing

The beggar prays to God

That he might catch some fish

The dog prays to the fish

That they might get caught.

(13)

December night

Taking a match stick from the beggar

She tries to light her cigarette.

(14)

Girl walks along the gaily-lit shops

And her perfume reminds the beggar

Of some of his own forgotten dreams.

(15)

The brown beggar comes to her door

and she screams : 'Do not disturb me now,

can you not see that I am praying?'

so he goes away wondering

to whom he should pray.

(16)

Even the bitterness of Spring

is a part of her beauty

in the city angry cars have become

rats that have forgotten their holes

only the sky now remembers

the cold weight of the black hunger.

(17)

When the horses come riding

riding through the December fog

dust and mist shall become one

and you shall then see

on her emaciated face

layer after layer

of terrified sunset.

(18)

Black train goes

rushing over the blacker rails

steel on steel

bone with bone

fire from fire

madness in madness

and after the train is gone

the rail tracks remain

as lonely

as speechless

as ever.

Now that the long winter nights become brighter than ever with halogen lights, here are eighteen of my songs for the Forgotten Darkness :

(1)

What does one beggar do

when another beggar comes to him

asking for money?

perhaps this is a meaningless question

or perhaps such things happen only in the movies

but as for my beggar

well, he can't do nothing at all

but stare into the eyes of his friend

while above both of them

the despicable winter sun

gently sinks into their tired eyes.

(2)

At the water's edge the beggar

sings the same song a million times

sometimes it is good

to hear your own voice

every noon the kite flies

round and round and round

screaming out her heart

for a fragile peace

that was never hers.

(3)

In this world

there are but three sorrows

one that is real

one that is unreal

and one that lies sleeping

in the abyss of your dark eyes

unknown even to you.

(4)

New year's Eve

the old beggar makes a fire

out of old lottery tickets

and on New year's Day

she changes the old water

in the vase with plastic flowers.

(5)

Christmas evening

The young man gives the beggar

His empty unused wallet.

(6)

Handing him a ten pound note

The girl asks the beggar

To give nine pounds back to her.

(7)

The old dog looks into the beggar’s bowl

And wonders which

Of the ten coins are for him.

(8)

The beggar has fifteen coins

He needs just one more

To teach his dog

How to play Chinese checkers.

(9)

Winter morning

At the temple

A long row of devotees

The beggar too takes out his three coins

And places them in a long row.

(10)

Busy market-square

The beggar and his violin

He is not very good at Mozart

But in this world

At least his dog has ears.

(11)

They say that the old temple

has now run out of priests

and I used to think

that there will be priests

as long as there are beggars.

(12)

Sunday afternoon

The beggar and his dog go fishing

The beggar prays to God

That he might catch some fish

The dog prays to the fish

That they might get caught.

(13)

December night

Taking a match stick from the beggar

She tries to light her cigarette.

(14)

Girl walks along the gaily-lit shops

And her perfume reminds the beggar

Of some of his own forgotten dreams.

(15)

The brown beggar comes to her door

and she screams : 'Do not disturb me now,

can you not see that I am praying?'

so he goes away wondering

to whom he should pray.

(16)

Even the bitterness of Spring

is a part of her beauty

in the city angry cars have become

rats that have forgotten their holes

only the sky now remembers

the cold weight of the black hunger.

(17)

When the horses come riding

riding through the December fog

dust and mist shall become one

and you shall then see

on her emaciated face

layer after layer

of terrified sunset.

(18)

Black train goes

rushing over the blacker rails

steel on steel

bone with bone

fire from fire

madness in madness

and after the train is gone

the rail tracks remain

as lonely

as speechless

as ever.

Living Along Fault-lines

My personal interest in that overburdened phrase ‘Islam and the West’ lies in the question of the relation between the two concepts of ‘religion’ and ‘culture’. Indeed, I believe that the ‘clash’ between Islam and the West ultimately revolves around different understandings of this relation. One way of investigation this relation is to start off by trying to define ‘religion’ and ‘culture’. However, as is well known to students of sociology and anthropology, this attempt can easily get bogged down in endless debate and controversy over what these concepts refer to. Therefore, I shall follow an alternative method : instead of trying to define these concepts, I shall outline the different ways in which people have, historically speaking, understood their mutual relation (or non-relation/anti-relation). Sometimes even when we cannot precisely define two terms A and B, an understanding of the relation between A and B can throw some light on what A and B themselves are.

A survey of the religious history of humanity reveals that there are four major ways in which the relation between ‘religion’ and ‘culture’ has been understood and put into socio-religious practice.

(A)

Religion Against Culture

This type emphasises the opposition between religion and culture. Whatever be the customs of the society in which the religious person lives, whatever be the human achievements that it conserves, religion is seen as being opposed to all of them. There is therefore a strict either-or between religion and culture. To be religious means that one must set his/her face completely against society.

Here are two examples :

(a) In the Graeco-Roman world, Christianity was totally opposed to what it perceived to be the idolatry of pagan culture. One of the popular Roman complaints against Christianity was that it was drawing young men and women from society and setting them against the ancient heritage of Greek civilisation. This was also true in the Mediaeval Ages when Christian monks and nuns rejected the world of culture as inherently corrupt and implicated in a sinister deal with devilish forces.

(b) Buddhism rejected the Brahmanic system of organisation of individual and social existence. With this rejection of casteism, went a whole-sale opposition to Brahmanic culture and everything that it entailed. The reason why Buddhism ultimately became a heterodox form of Hinduism was not because of its denial of the existence of 'God' (there were, and still are, Hindus who do not believe in 'God') but because of its opposition to contemporary culture. In other words, Buddhism was opposed not just to the Upanisadic-theological dimension of Hinduism but also to the cultural values it propagated.

(B)

Religion Of Culture

This type emphasises the fundamental agreement between religion and culture. A religious founder is regarded as the great hero of human culture and history and his (or her, in some rare cases) life and teachings are regarded as the greatest human achievement. It is believed that he brings to fulfilment the cultural aspirations of humankind. He confirms and supports whatever is best in culture and guides civilisation to its correct goal. Religion therefore is a part of culture in the sense that it includes the social heritage that must be transmitted and conserved.

Here are two examples :

(a) In the Mediaeval ages in Europe, the Catholic Church presented itself as fulfilling the best and the noblest elements in pagan culture. In other words, the Church emphasised that the teachings of Christianity brought contemporary culture into its proper fulfillment.

(b) Vedic Hinduism saw itself as providing the blue-print not only for religion but also for the varieties of cultural life. Indeed, for Vedic Hinduism, any separation between religion and culture was unknown. Culture was absorbed into religion and every cultural norm was legitimized through some religious practice or theological doctrine. For example, consider the question : is casteism a ‘religious’ or a ‘cultural’ system? From the perspective of Vedic Hinduism, one can only reply that this antithesis is misleading : casteism is at the same time both a religious and a cultural system.

(C)

Religion Above Culture

We now move into the third type. Those who follow this type agree with people in the second group on one point : religion is the fulfilment of culture. But they disagree with them on this point : there is a sharp discontinuity between religion and culture, and in this they agree with those in the first group. In other words, one cannot pass from religion and culture and vice versa as easily as in the case of, for example, Vedic Hinduism. There is therefore in religion something which does not follow immediately from culture. Religion is at the same time both continuous with and discontinuous with culture. Culture indeed leads men and women to religion but only in a partial, preliminary, and fragmented sense. A great leap is required if a person wants to move from culture to religion. True culture is possible only in the higher light of religious values.

Here are two examples :

(a) The ascetic tradition of Hinduism can be given as a good example of this type. Culture is not denounced as evil (as in the Type (A) above) but neither is there a direct step from culture to religion (as in the Type (B) above). Indeed, religion requires a rejection of certain elements of culture, which is good in itself (which is why the sannyasi is the world-renouncer), so that religious life requires a reordering of one’s value-system.

(b) Theravada Buddhism is another example of this type. In Thailand and Burma, Buddhism exists more or less harmoniously with various Hindu gods/goddesses and also belief in spirits (Burmese : nats). But it is emphasised repeatedly that the true Buddhist is not one who is immersed in the worship of gods and goddesses; the latter is a kind of ladder that one must throw away after one has reached the correct enlightenment. Thus Theravada Buddhism has a dialectical relation to the cultural life based on the Hinduism of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata : it both affirms the latter at a ‘lower’ level and rejects them at a ‘higher’ level.

(D)

Religion as Transformer of Culture

Those who fall in this group believe that religion has a conversionist function. We can better understand the claims of the people who belong to this group by contrasting their views with those of the previous ones.

In contrast to Type (A), those in this group argue that it is not enough simply to reject culture as devilish and move away from it. Rather, the diabolic elements in this culture must be transformed in the light of religious values.

In contrast to Type (B), it is argued that to say that one can move from culture to religion is to overlook the negative forms of injustice and inequalities that might be prevalent in culture. For example, slavery or patriarchy as a cultural institution can be uprooted only if there is some discontinuity between religion and culture. If religion is identified with culture without remainder, there remains no justification for opposing slavery or patriarchy.

In contrast to Type (C), it is argued that this answer is ultimately similar to Type (A). It is not enough to point out the discontinuities between religion and culture, the former should also be geared to removing the inequalities and the social injustices that are embodied in the latter.

With this survey, let me move on to make the following observations.

Though I started off by talking about Islam, it will be noticed that I have not mentioned Islam in any of the types so far. What we see from the above survey is that every religion has many strands in it, which is why we cannot claim that we have found the correct relation between a specific religion and culture. For example, I claimed that certain strands of Christianity can be placed in Type (A) (e.g.monastic Christianity) and other strands in Type (B) (e.g. the Holy Roman Empire). Similarly, there are elements of Hinduism which can be placed under Type (B) (e.g. Vedic Hinduism) and there are other elements in it which can be brought under Type (C) (e.g. ascetic Hinduism). In other words, we cannot provide a definite answer to this relation simply because no religion is a monolithic entity. There are complex strands within any religion and some of these strands may even contradict one another in certain respects. (To take just two examples, one can think of the endless debates over ‘idol-worship’ across the different traditions of Hinduism, and the question of whether Sufism is ‘orthodox’ Islam.)

What this means is also that we cannot say that there is only one way of conceptualising this relation in the case of Islam : we can place Islam both under Type (A) and Type (D). Islamic civilisation of the Baghdad Caliphate can perhaps be placed under Type (B). Type (A) is manifested in Islam’s vigorous denunciation (and destruction) of 'idol-worshipping' elements of surrounding culture. Type (D) is shown in the idea of an Islamic theocracy : every element of culture must be transformed in the light of Islamic doctrines.

Now one explanation for the strained relations between 'Islam and the West' is the following. ‘The West’, in general, has become very wary of systems that conceptualise the relation between ‘culture’ and ‘religion’ under Type (D). The notion that religion is a force that can transform culture is widely regarded as a reactionary one. Indeed, in the contemporary 'West', the preferred model seems to be some 'privatised' form of Type (B). Many a westerner will say : ‘I don’t care if you are religious so long as you do not go round disrupting and criticising my cultural values, whatever these may be. Religion is good as it is, but please do not let it interfere with my private life.’ This is something that Type (D) vigorously opposes : all cultural values without the light of religion are corrupt and vitiated by satanic forces.

In other words, one reason for the conflict between 'Islam and the West' is a difference of opinion over the importance that should be given to Type (D). ‘The West’ tends to reject Type (D) whereas it seems that Type (D) is almost required by the internal ‘logic’ of Islam. Islam is not, of course, the only religion that requires a Type (D) understanding of the relation between religion and culture : two other examples that come to mind immediately are John Calvin’s theocracy in Geneva and Ashokan Buddhism. Because of a long history of religious wars and oppression, however, ‘the West’ has made a decisive move away from Type (D) and religion has been stripped of all powers and channels to transform culture. A strict demarcation between the ‘religious’ and the ‘cultural’ spheres has been made : the former belongs to ‘private inner’ space and the latter to ‘public national’ space. In this situation, the rise of Islamic states under Type (D) which is regarded as confusing these two spaces heightens the opposition between ‘Islam and the West’.

I have said that the contemporary west broadly accepts Type (B). It looks at Type (A) as belonging to an age of persecution and religious tyranny. Now because of the conceptual similarity between Type (D) and Type (A), the 'West' feels that Islam can easily slip from Type (D) to Type (A), where Type (A) is equated with versions of ‘fundamentalisms’.

In truth, however, fundamentalism is possible even under Type (B). For example, contemporary Hindu fundamentalism is best placed not under Type (A) but under Type (B). Hindu fundamentalism does not reject culture but requires that it be absorbed into a certain specific understanding of what ‘Hinduism’ is. The problem is heightened by the fact that although critics of this fundamentalism can complain that Hinduism is being ‘politicised’, in truth there is no straightforward difference between ‘religion’, ‘culture’ and ‘politics’ in traditional Hinduism. Hindu fundamentalists can therefore claim that their interpretation of Hinduism is the traditional one, that is, in Hinduism, religion, culture and politics are intertwined. Another example of Type (B) relates to the socio-religious problems of the Middle East. The intimate connection between religion, land and culture in Israel and Palestine can be understood as a manifestation of this type.

To conclude then, I agree that an opposition between ‘Islam and the West’ is a genuine one. It is wrong, however, to think of this only as a modern contemporary phenomenon for it is as old as the Crusades. It is also wrong to think, however, that this opposition will always lead to ‘closure’ on all sides. The Mediaeval ages were the time of the Crusades, but they were also the time when a Moorish civilisation flourished. Indeed, Mediaeval Spain was one of the few times and places when Jews, Muslims and Christians lived together in harmony. This should not lead us to a facile optimism that another such culture will soon be formed, but it is only to serve as a reminder that oppositions need not always lead to a total breakdown in communication. Secondly, instead of talking about a clash between ‘civilisations’ one should rather talk about differences relating to the above types of conceptualising the relation between ‘religion’ and ‘culture’. ‘Civilisations’ do not exist in abstracto, they are not ‘things’ over and against people who have certain patterns of socio-religious behaviour, and indeed many of our problems begin precisely when we try to think of them as monolithic entities opposing one another.

My personal interest in that overburdened phrase ‘Islam and the West’ lies in the question of the relation between the two concepts of ‘religion’ and ‘culture’. Indeed, I believe that the ‘clash’ between Islam and the West ultimately revolves around different understandings of this relation. One way of investigation this relation is to start off by trying to define ‘religion’ and ‘culture’. However, as is well known to students of sociology and anthropology, this attempt can easily get bogged down in endless debate and controversy over what these concepts refer to. Therefore, I shall follow an alternative method : instead of trying to define these concepts, I shall outline the different ways in which people have, historically speaking, understood their mutual relation (or non-relation/anti-relation). Sometimes even when we cannot precisely define two terms A and B, an understanding of the relation between A and B can throw some light on what A and B themselves are.

A survey of the religious history of humanity reveals that there are four major ways in which the relation between ‘religion’ and ‘culture’ has been understood and put into socio-religious practice.

(A)

Religion Against Culture

This type emphasises the opposition between religion and culture. Whatever be the customs of the society in which the religious person lives, whatever be the human achievements that it conserves, religion is seen as being opposed to all of them. There is therefore a strict either-or between religion and culture. To be religious means that one must set his/her face completely against society.

Here are two examples :

(a) In the Graeco-Roman world, Christianity was totally opposed to what it perceived to be the idolatry of pagan culture. One of the popular Roman complaints against Christianity was that it was drawing young men and women from society and setting them against the ancient heritage of Greek civilisation. This was also true in the Mediaeval Ages when Christian monks and nuns rejected the world of culture as inherently corrupt and implicated in a sinister deal with devilish forces.

(b) Buddhism rejected the Brahmanic system of organisation of individual and social existence. With this rejection of casteism, went a whole-sale opposition to Brahmanic culture and everything that it entailed. The reason why Buddhism ultimately became a heterodox form of Hinduism was not because of its denial of the existence of 'God' (there were, and still are, Hindus who do not believe in 'God') but because of its opposition to contemporary culture. In other words, Buddhism was opposed not just to the Upanisadic-theological dimension of Hinduism but also to the cultural values it propagated.

(B)

Religion Of Culture

This type emphasises the fundamental agreement between religion and culture. A religious founder is regarded as the great hero of human culture and history and his (or her, in some rare cases) life and teachings are regarded as the greatest human achievement. It is believed that he brings to fulfilment the cultural aspirations of humankind. He confirms and supports whatever is best in culture and guides civilisation to its correct goal. Religion therefore is a part of culture in the sense that it includes the social heritage that must be transmitted and conserved.

Here are two examples :

(a) In the Mediaeval ages in Europe, the Catholic Church presented itself as fulfilling the best and the noblest elements in pagan culture. In other words, the Church emphasised that the teachings of Christianity brought contemporary culture into its proper fulfillment.

(b) Vedic Hinduism saw itself as providing the blue-print not only for religion but also for the varieties of cultural life. Indeed, for Vedic Hinduism, any separation between religion and culture was unknown. Culture was absorbed into religion and every cultural norm was legitimized through some religious practice or theological doctrine. For example, consider the question : is casteism a ‘religious’ or a ‘cultural’ system? From the perspective of Vedic Hinduism, one can only reply that this antithesis is misleading : casteism is at the same time both a religious and a cultural system.

(C)

Religion Above Culture

We now move into the third type. Those who follow this type agree with people in the second group on one point : religion is the fulfilment of culture. But they disagree with them on this point : there is a sharp discontinuity between religion and culture, and in this they agree with those in the first group. In other words, one cannot pass from religion and culture and vice versa as easily as in the case of, for example, Vedic Hinduism. There is therefore in religion something which does not follow immediately from culture. Religion is at the same time both continuous with and discontinuous with culture. Culture indeed leads men and women to religion but only in a partial, preliminary, and fragmented sense. A great leap is required if a person wants to move from culture to religion. True culture is possible only in the higher light of religious values.

Here are two examples :

(a) The ascetic tradition of Hinduism can be given as a good example of this type. Culture is not denounced as evil (as in the Type (A) above) but neither is there a direct step from culture to religion (as in the Type (B) above). Indeed, religion requires a rejection of certain elements of culture, which is good in itself (which is why the sannyasi is the world-renouncer), so that religious life requires a reordering of one’s value-system.

(b) Theravada Buddhism is another example of this type. In Thailand and Burma, Buddhism exists more or less harmoniously with various Hindu gods/goddesses and also belief in spirits (Burmese : nats). But it is emphasised repeatedly that the true Buddhist is not one who is immersed in the worship of gods and goddesses; the latter is a kind of ladder that one must throw away after one has reached the correct enlightenment. Thus Theravada Buddhism has a dialectical relation to the cultural life based on the Hinduism of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata : it both affirms the latter at a ‘lower’ level and rejects them at a ‘higher’ level.

(D)

Religion as Transformer of Culture

Those who fall in this group believe that religion has a conversionist function. We can better understand the claims of the people who belong to this group by contrasting their views with those of the previous ones.

In contrast to Type (A), those in this group argue that it is not enough simply to reject culture as devilish and move away from it. Rather, the diabolic elements in this culture must be transformed in the light of religious values.

In contrast to Type (B), it is argued that to say that one can move from culture to religion is to overlook the negative forms of injustice and inequalities that might be prevalent in culture. For example, slavery or patriarchy as a cultural institution can be uprooted only if there is some discontinuity between religion and culture. If religion is identified with culture without remainder, there remains no justification for opposing slavery or patriarchy.

In contrast to Type (C), it is argued that this answer is ultimately similar to Type (A). It is not enough to point out the discontinuities between religion and culture, the former should also be geared to removing the inequalities and the social injustices that are embodied in the latter.

With this survey, let me move on to make the following observations.

Though I started off by talking about Islam, it will be noticed that I have not mentioned Islam in any of the types so far. What we see from the above survey is that every religion has many strands in it, which is why we cannot claim that we have found the correct relation between a specific religion and culture. For example, I claimed that certain strands of Christianity can be placed in Type (A) (e.g.monastic Christianity) and other strands in Type (B) (e.g. the Holy Roman Empire). Similarly, there are elements of Hinduism which can be placed under Type (B) (e.g. Vedic Hinduism) and there are other elements in it which can be brought under Type (C) (e.g. ascetic Hinduism). In other words, we cannot provide a definite answer to this relation simply because no religion is a monolithic entity. There are complex strands within any religion and some of these strands may even contradict one another in certain respects. (To take just two examples, one can think of the endless debates over ‘idol-worship’ across the different traditions of Hinduism, and the question of whether Sufism is ‘orthodox’ Islam.)

What this means is also that we cannot say that there is only one way of conceptualising this relation in the case of Islam : we can place Islam both under Type (A) and Type (D). Islamic civilisation of the Baghdad Caliphate can perhaps be placed under Type (B). Type (A) is manifested in Islam’s vigorous denunciation (and destruction) of 'idol-worshipping' elements of surrounding culture. Type (D) is shown in the idea of an Islamic theocracy : every element of culture must be transformed in the light of Islamic doctrines.

Now one explanation for the strained relations between 'Islam and the West' is the following. ‘The West’, in general, has become very wary of systems that conceptualise the relation between ‘culture’ and ‘religion’ under Type (D). The notion that religion is a force that can transform culture is widely regarded as a reactionary one. Indeed, in the contemporary 'West', the preferred model seems to be some 'privatised' form of Type (B). Many a westerner will say : ‘I don’t care if you are religious so long as you do not go round disrupting and criticising my cultural values, whatever these may be. Religion is good as it is, but please do not let it interfere with my private life.’ This is something that Type (D) vigorously opposes : all cultural values without the light of religion are corrupt and vitiated by satanic forces.

In other words, one reason for the conflict between 'Islam and the West' is a difference of opinion over the importance that should be given to Type (D). ‘The West’ tends to reject Type (D) whereas it seems that Type (D) is almost required by the internal ‘logic’ of Islam. Islam is not, of course, the only religion that requires a Type (D) understanding of the relation between religion and culture : two other examples that come to mind immediately are John Calvin’s theocracy in Geneva and Ashokan Buddhism. Because of a long history of religious wars and oppression, however, ‘the West’ has made a decisive move away from Type (D) and religion has been stripped of all powers and channels to transform culture. A strict demarcation between the ‘religious’ and the ‘cultural’ spheres has been made : the former belongs to ‘private inner’ space and the latter to ‘public national’ space. In this situation, the rise of Islamic states under Type (D) which is regarded as confusing these two spaces heightens the opposition between ‘Islam and the West’.

I have said that the contemporary west broadly accepts Type (B). It looks at Type (A) as belonging to an age of persecution and religious tyranny. Now because of the conceptual similarity between Type (D) and Type (A), the 'West' feels that Islam can easily slip from Type (D) to Type (A), where Type (A) is equated with versions of ‘fundamentalisms’.

In truth, however, fundamentalism is possible even under Type (B). For example, contemporary Hindu fundamentalism is best placed not under Type (A) but under Type (B). Hindu fundamentalism does not reject culture but requires that it be absorbed into a certain specific understanding of what ‘Hinduism’ is. The problem is heightened by the fact that although critics of this fundamentalism can complain that Hinduism is being ‘politicised’, in truth there is no straightforward difference between ‘religion’, ‘culture’ and ‘politics’ in traditional Hinduism. Hindu fundamentalists can therefore claim that their interpretation of Hinduism is the traditional one, that is, in Hinduism, religion, culture and politics are intertwined. Another example of Type (B) relates to the socio-religious problems of the Middle East. The intimate connection between religion, land and culture in Israel and Palestine can be understood as a manifestation of this type.

To conclude then, I agree that an opposition between ‘Islam and the West’ is a genuine one. It is wrong, however, to think of this only as a modern contemporary phenomenon for it is as old as the Crusades. It is also wrong to think, however, that this opposition will always lead to ‘closure’ on all sides. The Mediaeval ages were the time of the Crusades, but they were also the time when a Moorish civilisation flourished. Indeed, Mediaeval Spain was one of the few times and places when Jews, Muslims and Christians lived together in harmony. This should not lead us to a facile optimism that another such culture will soon be formed, but it is only to serve as a reminder that oppositions need not always lead to a total breakdown in communication. Secondly, instead of talking about a clash between ‘civilisations’ one should rather talk about differences relating to the above types of conceptualising the relation between ‘religion’ and ‘culture’. ‘Civilisations’ do not exist in abstracto, they are not ‘things’ over and against people who have certain patterns of socio-religious behaviour, and indeed many of our problems begin precisely when we try to think of them as monolithic entities opposing one another.

Wednesday, December 29, 2004

The Heart of Emptiness

(1)

Who shall know when suffering shall end ?

Perhaps suffering is just another illusion?

What, then, shall I tell them ---

They who spend autumn evenings

On the other side of those mountains

Weaving garlands out of the fallen flowers?

(2)

Is there no way

Out of the great circle of doubt?

Perhaps the only answer

Is the silent bridge

Over the noisy chasm

Some shall cross it

Others shall say

That the bridge does not exist

And yet perhaps the bridge itself shall remain

Till the last traveller in this world has turned to dust.

(1)

Who shall know when suffering shall end ?

Perhaps suffering is just another illusion?

What, then, shall I tell them ---

They who spend autumn evenings

On the other side of those mountains

Weaving garlands out of the fallen flowers?

(2)

Is there no way

Out of the great circle of doubt?

Perhaps the only answer

Is the silent bridge

Over the noisy chasm

Some shall cross it

Others shall say

That the bridge does not exist

And yet perhaps the bridge itself shall remain

Till the last traveller in this world has turned to dust.

The Death of God

Is God dead?