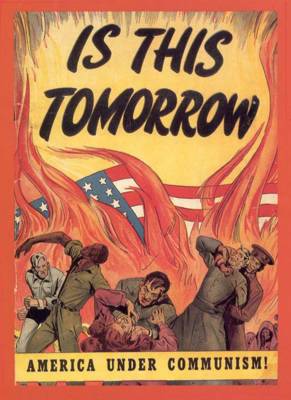

One dictionary defines the phrase 'red herring' as something that draws attention away from the central issue, and tells us that the origin of this expression is the practice of dragging a smoked herring along a track so as to throw off tracking dogs. The fear of the spread of 'Communism' acted as one such red herring during the McCarthy era in the US : instead of asking crucial questions such as what 'communism' was, and what its historical origins, socio-economic principles, and vision of human destiny were (which was the 'central issue'), the US administration tried to rouse the hysteria of the people against the Reds. It is arguable that in the late 1990s, the term Toleration has become the red herring for us with respect to various issues : rather than asking what these issues are really about, to what extent the claims associated with them are in/valid, how people whose lives are directly affected by them view them, and what inter-connected configurations of socio-economic-cultural questions these issues raise in their wake, we often behave as lazy school-children and try to wash our hands off such difficult home-work under the illusion that our laziness is justified by appealing to (an ill-defined) Tolerance.

Since, as an Old Master said, the beginning of wisdom lies in the definition of terms, I shall make one attempt towards 'wisdom' by first defining Toleration. I shall call a certain person to be tolerant of a belief or practice if she : (a) recognises that it is genuinely different from beliefs and practices located in her own world-view, (b) disagrees with the former, (c) and yet provides some space for the former to develop. Let us now apply this definition to two examples.

(1) To be 'tolerant' of Islam, it will not therefore do to go around entertaining vague notions of what Muslims believe and practice; nor can one say that the mere act of sharing a meal, watching a film, going to the same university, or playing a football match with a Muslim in itself amounts to 'toleration' (it goes without saying that the latter activities are most welcome, but they do not constitute toleration as I understand the term here). A person, David, can be said to be tolerant of a Muslim only when he first undertakes a careful study of the principles of Islam and develops some acquaintance with believers who practise these, and thereby comes to know what the precise differences are between his world-view and the life form called Islam. It may happen that in the process David realises that he and his Muslim acquaintance are living in two worlds separated by a wide chasm over several issues, and this will lead both of them to (re-)examine the validity of the claims that are raised in each other's world-views. In spite of these (possible) crucial differences, David must be willing to make some space, socially, culturally and legally, so as to ensure that the Muslim is able to live and flourish in the latter's religious world.

(2) To take an example from the other end of the spectrum, another person, Imran, can be said to be 'tolerant' of an atheist only when he is patient enough to know what the atheist really believes in (or disbelieves in), and how she lives in accordance with these dis/beliefs. To (apparently) live in harmony with an atheist, greeting her with a polite smile every morning, having coffee with her at the mid-day break, and going to the movies with her every weekend, while believing inwardly that she is morally corrupt or eternally damned, is not toleration but paternalism. To be truly tolerant of each other, both of them must engage themselves in a mutual process of (re-)examining the truth-claims that they respectively make within the horizons of their own worlds, and ask each other the hard, unsettling, and difficult questions that go with such (re-)examinations. To claim that they are 'tolerating' each other without having engaged in such investigations would be a parody of that term; this is but a thin and fragile 'tolerance' which can be used a mask for disguising the deep hatred and mutual distrust that may lie within. Finally, after such mutual inquiries, Imran must be willing to allow his atheist friend some conceptual and social space wherein she can develop her atheist convictions and live in accordance with them.

What have we observed in the above analysis? Firstly, the notion of tolerating someone must be carefully distinguished from the attitude that goes by the slogan : 'I do my thing, and you do your thing. Let us not disturb each other'. This slogan refers to a static state of affairs, a stalemate or a standoff between two parties, whereas toleration refers to an ongoing process, a never-ending dialogue between them. If I, who am religious, am to truly tolerate an atheist friend, it means that (a) I believe that she is mistaken in holding some of her beliefs, (b) wish, nevertheless, to engage her in a continuous dialogue over these beliefs, (c) and yet am willing to allow her space to develop her views. Toleration, as I understand the term, is therefore not a passive state but an active response, a desire to learn more about the other, and this is the reason why (b) is important. I am said to truly tolerate members of communities to which I do not belong only when I simultaneouly affirm (a), (b), and (c). To accept (b) and (c) without (a) would mean that I am shying away from the hard home-work of analysing truth-claims, to accept (a) and (c) without (b) would mean that I am hiding my lack of desire to know the other under the cloak of 'toleration', and finally to accept (a) and (b) without (c) would mean that I view the others as a constant threat at my horizons and cannot coexist with their otherness.

In short, I understand 'toleration' and 'dia-logue' as co-terminous, which is to say that I truly tolerate only those people with whom I am engaged in a constant dialogue. For example, I cannot be said, strictly speaking, to tolerate Tibetan Buddhists, anti-abortionists, Japanese Shintoists, or Chinese communists. The reason for this is not because I wish to exterminate them or cast them into cold dungeons (I do not) but because I do not know anyone belonging to any of the above communities, and, therefore, cannot obviously enter into a living dia-logue with them. I can, of course, still say that I tolerate Tibetan Buddhists but this 'toleration' would only be in a trivial and formally empty sense. On the other hand, I can say that I tolerate Anglican Christians, Marxists, Buddhists, agnostics, and atheists because not only do I know some Anglican, Marxist, Buddhists, agnostic, and atheist friends but also because I am engaged, every now and then, in a mutual process of discussing their views with mine.

Indeed, the slogan, 'I do my own thing, you do yours', far from being a manifestation of 'tolerance' can be used to mask pernicious forms of seething underlying hatred. In saying this, I do not imply that we must jump to the other extreme slogan which goes as, 'I know it better than you do', and which tries to legitimise all sorts of 'interventionist' activity. All of this brings out the dire need of (c); we must be willing, in spite of our mutual differences, some of which can be radical, to engage ourselves in the never-ending process of (re-)negotiating and (re-)establishing the social and cultural boundaries which mark off certain zones as belonging to 'us' and 'them'. This process can be given the shorthand term 'toleration'.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home