Last night, I dreamt that I was in Cambridge again, but this was not the same Cambridge from which I had matriculated in 1998. Gone were the dreaming spires rising up into the transparent sky, the blue flags fluttering breezily in the nippy air, the clock with its deep chimes resonating down the hollow corridors, and the polished green grass shining in the mellow autumn sunlight. Instead, I found myself in a gigantic hall that was brilliantly lit from all corners with a number of lights of different colours, red, blue, green, purple, and yellow. I saw a number of my old college friends, and they all came running up to me with the same remark, 'I just read your autobiography. It is awesome.' To all of them, I gave the same reply, 'My autobiography? Where on earth did you read that?, and they retorted, 'Why, it is there in your pigeon-hole at the other end of the hall!'

Saturday, March 05, 2005

An anonymous reader of this blog had made a request yesterday that the Transparent Ironist publish his signature as one of his posts. Since he does not have access to a scanner at the moment, he is instead publishing one of his dreams here. This is because he believes that an analysis of this single dream will take the reader much closer to who he 'really is' than any number of dissections of his signatures.

Last night, I dreamt that I was in Cambridge again, but this was not the same Cambridge from which I had matriculated in 1998. Gone were the dreaming spires rising up into the transparent sky, the blue flags fluttering breezily in the nippy air, the clock with its deep chimes resonating down the hollow corridors, and the polished green grass shining in the mellow autumn sunlight. Instead, I found myself in a gigantic hall that was brilliantly lit from all corners with a number of lights of different colours, red, blue, green, purple, and yellow. I saw a number of my old college friends, and they all came running up to me with the same remark, 'I just read your autobiography. It is awesome.' To all of them, I gave the same reply, 'My autobiography? Where on earth did you read that?, and they retorted, 'Why, it is there in your pigeon-hole at the other end of the hall!'

I rushed down to the brightly-lit rows of pigeon-holes, and desperately tried to find my initials. When I eventually found my pigeon-hole, I looked into it but could find no autobiography there. I ran back and started asking those friends if they had really seen my autobiography there, and they all assured me that they had read it there just a couple of hours ago. I frantically dashed back to the pigeon-hole, but could not find it this time either.

I woke up this morning in a cold sweat and found my beautiful black dog lavishly licking my face, trying to wake me up. I rushed downstairs and told my grey-haired housekeeper at the door that I had no time for breakfast, leaving her faintly muttering something about how self-absorbed and solipsistic men had become these days. I went to my office, and my secretary told me with a twinkle in her blue eyes that there was something waiting for me in my pigeon-hole. It was a sweet-smelling neat brown package, and I opened it hurriedly : it was a fresh copy of my autobiography from my publisher with a note from her inside it, 'Dear Mr Ironist, I hope you shall now finally find yourself.'

Friday, March 04, 2005

A Note For My Readers

The Transparent Ironist hereby wishes to notify his readers that there will be no edition of his blog today and tomorrow morning since he shall be busy writing a long letter to Dr Gayatri Spivak Chakravorty. Dr Chakravorty had published an influential essay in 1988 called 'Can The Subaltern Speak?' in which she had announced, not surprisingly, that subaltern (= silenced) women cannot speak, in the sense that they are shadowy and marginalised figures whose voices cannot be properly interpreted or received by others. In the light of the enthusiastic response that he has been receiving to the predicament of his cousin Ms Shefali Raha (see the post immediately below this one), however, the Transparent Ironist sees a ray of hope in the encircling gloom, and is inspired to believe that some subaltern women are increasingly making themselves understood (no?). He shall therefore write to Dr Chakravorty that when she had written her essay way back in 1988 she could not have foreseen the emergence of www.realappearance.blogspot.com as an eloquent medium through which such subaltern women could attempt, even if attempt only to fail, the risky task of making themselves heard as they seek to free themselves from the oppressive tentacles of the sinister Family. (If you have any personal comments for Dr Chakravorty and want me to include them in my letter to her, please feel free to leave them here before 6 : 00 pm Eastern Standard Time, Saturday 5.)

Thursday, March 03, 2005

The Subaltern Desire Of My Calcutta Cousin

I was talking on the phone yesterday to my cousin Shefali Raha (no relation, so far as I know, to the other Raha in my life, Shomikho Raha), and it is at her request that I am writing about her on this blog today, with the hope that some of you might be able to help her out. Even if you are not familiar in any way with India, there is something that tells me that Shefali's dilemma is quite trans-national (and is even, dare I say it, 'universal'). Shefali was born and brought up in north Calcutta, and came to Delhi at the age of 16 where she received her college education and where she now works for a law firm in South Extension. Shefali is a fiercely 'independent' woman who has suddenly realised that the men became independent as long ago as 1947, she is highly suspicious of any 'absolutist' views, and she is in fact quite the 'modern Indian woman', a label which, depending on who your potential buyer is, can either enhance or reduce your value in the Indian marriage-market. Just for your perusal, here are some vital facts gleaned from Shefali's profile (deduced, of course, with her permission).

Name : Shefali Raha

Age : 29

Religion : Surely you must be joking?

Marital Status : Not applicable

Sense of Humour : Serious

Books : Mature(d), Textured, Sophisticated

Best friend : My dog Chow-chow

Name : Shefali Raha

Age : 29

Religion : Surely you must be joking?

Marital Status : Not applicable

Sense of Humour : Serious

Books : Mature(d), Textured, Sophisticated

Best friend : My dog Chow-chow

Food : Macher jhol (cannot be translated into English for problems of incommensurability)

Political affiliation(s) : Left-wing to Wing-less

Fashion : Khadi jeans, hemp denims, and jute skirts

Living : With myself, and even that is one person too many at times

Music : Any music that I can face

Although Shefali has now spent thirteen years in Delhi, she still misses home and her family dearly, and sometimes desperately wants to go back, a wish that she refers to as her Subaltern Desire. For her, 'home' is a space from which she originated, the ground where her roots firmly remain, and a zone of security, comfort, and stability. In Delhi, she suffers from a feeling of rootlessness, and she fondly thinks of her childhood and the myriad images associated with her years of growing up with the sights, the smells, and the sounds of suburban Calcutta.

She feels tired of having to live like a migrant perennially on the move, for she dwells in a precarious zone that is in-between her Bengali relatives in Delhi and her non-Bengali friends. When she is with her relatives in Chittaranjan Park, she experiences feelings of 'home', of 'belonging', and of being 'in place', and the security of having a stable identity, but she knows only too well that to be accepted by her non-Bengali friends as an authentic member of their group she must suppress whatever they might connect, rightly or wrongly, with her Bengali-ness, food, dress, and music included.

Consequently, for Shefali the certainty of belonging to fixed and stable roots is a luxury, and her life in Delhi is instead an ever-shifting and mobile kaleidoscope of various photographs, sounds, newspapers, promises, tears, bus-journeys, violences, films, taunts, rainbows, monsoon-showers, stories, beliefs, book-stores, quarrels, abuses, dust-storms, gains, and losses. Everything comes to her in partial fragments, and she has to patch them together every morning into a contingent configuration that will see her through the day. In this manner, her identity is being constantly challenged, dissolved, and remade, and she struggles hard to maintain some degree of continuity between her past, her present, and her future through the different patch-works that she knits together every day.

No wonder, then, that Shefali wishes so much to go back home to her family in Calcutta. And yet, this is where an ironic twist comes into her story. For no sooner has she spent seven days with her family that she fervently wishes to go back to the vast swirling anonymous masses of Delhi's rush-hour traffic. She feels trapped in the claustrophobic atmosphere that she finds at home, and her rising irritation with her parents is increased ten-fold when she has to visit with them her relatives who she thinks are outdated, superstitious, and reactionary, and quite frankly, simply stupid, miserably moronic, and impossibly idiotic. Consequently, whenever she is in Calcutta she yearns to run back to Delhi, the very same Delhi that had seemed so ghastly, uncouth, intimidating, and uncivilised a place just seven days earlier. Calcutta becomes one black hole stifling her individuality, her freedom and her creativity, and she seeks the solace of the masses of Delhi in whose midsts she can revel in and celebrate her 'space', her distinctiveness and her hybridity.

Do you see anything of yourself in Shefali (or anything of her in yourself)? Do you too experience occasional bouts of this Subaltern Desire, a Desire that you are unable to admit to the other self-styled atomised individuals around you? Do you feel pulled apart along two opposite directions, one between an affirmation of your 'private space' where you can flourish and a negation of this very space through an absorption into the wider circle of your family? Have you devised any methods, or gathered any tools for dealing with this urban paradox?

Political affiliation(s) : Left-wing to Wing-less

Fashion : Khadi jeans, hemp denims, and jute skirts

Living : With myself, and even that is one person too many at times

Music : Any music that I can face

Although Shefali has now spent thirteen years in Delhi, she still misses home and her family dearly, and sometimes desperately wants to go back, a wish that she refers to as her Subaltern Desire. For her, 'home' is a space from which she originated, the ground where her roots firmly remain, and a zone of security, comfort, and stability. In Delhi, she suffers from a feeling of rootlessness, and she fondly thinks of her childhood and the myriad images associated with her years of growing up with the sights, the smells, and the sounds of suburban Calcutta.

She feels tired of having to live like a migrant perennially on the move, for she dwells in a precarious zone that is in-between her Bengali relatives in Delhi and her non-Bengali friends. When she is with her relatives in Chittaranjan Park, she experiences feelings of 'home', of 'belonging', and of being 'in place', and the security of having a stable identity, but she knows only too well that to be accepted by her non-Bengali friends as an authentic member of their group she must suppress whatever they might connect, rightly or wrongly, with her Bengali-ness, food, dress, and music included.

Consequently, for Shefali the certainty of belonging to fixed and stable roots is a luxury, and her life in Delhi is instead an ever-shifting and mobile kaleidoscope of various photographs, sounds, newspapers, promises, tears, bus-journeys, violences, films, taunts, rainbows, monsoon-showers, stories, beliefs, book-stores, quarrels, abuses, dust-storms, gains, and losses. Everything comes to her in partial fragments, and she has to patch them together every morning into a contingent configuration that will see her through the day. In this manner, her identity is being constantly challenged, dissolved, and remade, and she struggles hard to maintain some degree of continuity between her past, her present, and her future through the different patch-works that she knits together every day.

No wonder, then, that Shefali wishes so much to go back home to her family in Calcutta. And yet, this is where an ironic twist comes into her story. For no sooner has she spent seven days with her family that she fervently wishes to go back to the vast swirling anonymous masses of Delhi's rush-hour traffic. She feels trapped in the claustrophobic atmosphere that she finds at home, and her rising irritation with her parents is increased ten-fold when she has to visit with them her relatives who she thinks are outdated, superstitious, and reactionary, and quite frankly, simply stupid, miserably moronic, and impossibly idiotic. Consequently, whenever she is in Calcutta she yearns to run back to Delhi, the very same Delhi that had seemed so ghastly, uncouth, intimidating, and uncivilised a place just seven days earlier. Calcutta becomes one black hole stifling her individuality, her freedom and her creativity, and she seeks the solace of the masses of Delhi in whose midsts she can revel in and celebrate her 'space', her distinctiveness and her hybridity.

Do you see anything of yourself in Shefali (or anything of her in yourself)? Do you too experience occasional bouts of this Subaltern Desire, a Desire that you are unable to admit to the other self-styled atomised individuals around you? Do you feel pulled apart along two opposite directions, one between an affirmation of your 'private space' where you can flourish and a negation of this very space through an absorption into the wider circle of your family? Have you devised any methods, or gathered any tools for dealing with this urban paradox?

Wednesday, March 02, 2005

The Great Dilemma

I have been reading the autobiography of the English novelist Emmanuelle Wallerstein, and she writes about a dilemma that she was facing during the last five years of her life before she was killed in a car crash in Tokyo. Here are some excerpts from her autobiography published posthumously :

'I was born in London of the late 1960s, a heady period especially with all those violent winds blowing in from the other side of the English channel. My family, however, managed to shelter me from them, and I grew up blissfully on a diet of McDonald's, Burger King, and Starbucks every evening, and with a collection from all the chic labels from the High Streets of London...

'It was in 1994 that I met Angela for the first time, and she impressed upon me that I should stop going to Starbucks for my coffee. She told that this coffee-chain exploited millions of poor coffee-bean growers in parts of Latin America, and bought their coffee without paying them a fair deal in return. I was so astonished on hearing this that I forthwith decided to stop going to Starbucks, and instead started making my own coffee from the next day with the world's favourite coffee, Nescafe. Three months later, however, when I met Angela again, she told me that I should not buy that either since it was produced by a multi-national giant called Nestle. Consequently, I stopped drinking coffee altogether, for I was unable to find any coffee on the market that was not a product of some corporate body or the other...

'Soon I began to realise that I would have to change my life drastically. Firstly, I would not be able to shop anymore in the supermarkets, since all of them were but small links in gigantic global chains which exploited or oppressed people in some part of the world or the other. Everyone of us was complicit in these bonds , and we were all mutually implicated in ever-expanding circles of shared responsibility for what we had done to our planet. Secondly, I realised that I would not be able to have any babies either. Not that I ever had any fondness for them (I have always been indifferent to babies), but this time the truth hit me straight in the face. If I were to have a baby, I would have to buy medicines from some multi-national corporation, and even baby-food is produced by one of these international rings. Not only that, my baby would be using up resources that were already scarce, and by bringing another human being into this world I would only be augmenting the problem of global hunger and magnifying the current levels of economic disparity...

'It was around this time that I read about a man called Henry David Thoreau, and I decided to start living like him in a wooden hut in a village far away from civilisation. There I lived with no electricity, no radios, no TVs, and indeed no mode of communication with the external world. I grew my own food on the patch of land behind my hut, and drank water from the natural streams in the hills nearby. I would weave my own cloth from cotton that I grew along with my potatoes, carrots, radishes, and lettuces. Every morning, I woke up to the delightful songs of the birds to see the Hunter of the Morning, the Sun, shooting His mighty rays into the distant horizons and dispelling to the furthest corners the abominable forces of Darkness. Every day, I blissfully communed with Mother Nature from whose bosom I had been violently estranged by the demoniacal forces of the man-made Machine...

'I lived in these placid surroundings for two years, and would probably have continued to do so for the rest of my life had not Angela come to see me one evening in the manner of a sinister cloud slowly creeping into my green valley. Angela was shocked to find me slumbering there so far away from the madding crowd. She accused me of all sorts of terrible things; that I was a coward, an escapist, a dreamer, a romantic, a utopian, and a stargazer. She blamed me for being so utterly morally irresponsible and of shrinking into myself when millions of people out there were dying of hunger, starvation, and such miseries. She urged me to return to the world, the very same world that I had rejected three years ago because I had felt that it was criss-crossed by global chains of callousness, bestiality, and exploitation, chains from which I could never break free. Truly, woman is born in chains, but everywhere she wants to become free...'

So, then, that is all for today; I shall continue to add some more excerpts from her autobiography now and then. Quite a strange journey, I must say : from the world, away from it, and then back to it.

Nations are viewed as masculine or feminine (Germany the Fatherland, India the Motherland); one's native or first tongue, however, always seems to be conceptualised as feminine as one's mother tongue. From a historical perspective, this is not very surprising since in most epochs women have been regarded not only as the material or biological reproducers of children, who will later be introduced into the 'correct' way of life with the established rites, but also the symbolic transmitters of the heritage and the norms of their culture. Traditionally, therefore, women exist at the ambivalent intersection between 'nature' and 'culture', and they are represented as 'authentically' feminine only to the extent that they are able to properly fulfil this dual role of being both biological and cultural reproducers.

Tuesday, March 01, 2005

The Location Of Suffering

I had a rather curious string of experiences yesterday evening. One of my professors Dr Joachim Rosenthal was releasing his second book The Location of Suffering (Kalamazoo, 2005) at the Cambridge University Centre, and though I was feeling a bit sleepy I decided to go along since I had already paid 15 pounds for the ceremony. There was a huge gathering in the auditorium flush with yellow lights, most of them seemed to be students but there were also a few much older people. Dr Rosenthal welcomed everyone and enthusiastically started talking about some of the important themes of his book. He argued that 'suffering' cannot be located anywhere precisely because it cannot be specified, described, or pinned down to one set of experiences. Indeed, using a suggestive metaphor, he said that trying to define the term 'suffering' was like attempting to catch a slippery eel with hands covered with soap. He concluded by saying that his book should rather have been titled The Dis-locations of Suffering, but that it had already been sent to the press when he had arrived at this realisation.

I had a rather curious string of experiences yesterday evening. One of my professors Dr Joachim Rosenthal was releasing his second book The Location of Suffering (Kalamazoo, 2005) at the Cambridge University Centre, and though I was feeling a bit sleepy I decided to go along since I had already paid 15 pounds for the ceremony. There was a huge gathering in the auditorium flush with yellow lights, most of them seemed to be students but there were also a few much older people. Dr Rosenthal welcomed everyone and enthusiastically started talking about some of the important themes of his book. He argued that 'suffering' cannot be located anywhere precisely because it cannot be specified, described, or pinned down to one set of experiences. Indeed, using a suggestive metaphor, he said that trying to define the term 'suffering' was like attempting to catch a slippery eel with hands covered with soap. He concluded by saying that his book should rather have been titled The Dis-locations of Suffering, but that it had already been sent to the press when he had arrived at this realisation.

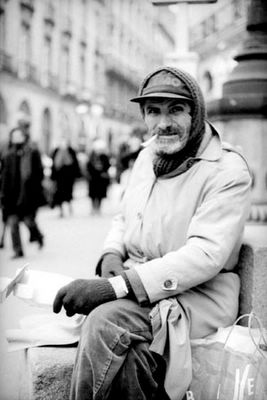

I came out of the meeting feeling a bit dazed with Dr Rosenthal's brilliant dissection of suffering and his mesmerising use of a detailed conceptual vocabulary that he had invented for the purpose of his book. As I was about to turn towards Trinity, I saw an old man with his black dog sitting down under an oak tree just beside the river Cam, and as I approached him I saw that he was gathering some bits and pieces of wood from the damp grass. He collected all of them into one heap, lit them up with a matchstick, and sat down beside the fire along with his faintly whimpering dog. Seeing me standing and staring at him, he beckoned to me to come closer to him and sit down alongside him. As I sat there in the rapidly falling dusk, I saw him looking at the black hard-bound book in my hand.

'You want to read my book?'

He gently shook his head.

'You want to take my book?'

He shook his head again.

'You want to burn my book?', I asked him, though I do not really know what made me ask him that question.

His eyes suddenly flashed in the evening darkness, a smile came over his faint lips, and he peered at me for a long moment. Then he hungrily seized the book from me, tore off the cover, and threw it into the fire. I watched, paralysed to the bone : that book had cost me 35 pounds and would not be available in the Library for at least another five months. He did not stop, however, and frantically went on tearing off the pages and casting them into the luminous heap of paper and wood.

Behind me, the dog was wagging its tail wildly and in the skies above, a few snow-flakes were drifting in the cold air. It was only then that I finally realised why suffering cannot be located : it is both everywhere and nowhere, it is a bundle of paradoxes, it is infinitely beyond us and is yet present to us intimately as the most tangible reality, we desperately wish to run away from it and yet are somehow afraid to lose its strange warmth.

The old man was now rubbing his hands in glee, and his face was shining as brightly as the crackling mass. I looked once again into his dark eyes. There the sigh of my disinherited Mind had finally become one with the lament of his dispossessed World.

Monday, February 28, 2005

Star-Crossed Debates

Should Astrology be taught in Indian universities and, in addition, should this subject earn government patronage when funds for other subjects are (already) scarce? Opinions are sharply divided on this question, and discussions involving it can easily descend into the unsavoury business of exchanging abuses. On the one hand, there are those who armed with the arsenal of Science launch their flaming torches at the dark forces represented by the superstitious and devious practitioners of Astrology. On the other hand, their redoubtable opponents reply that Astrology deserves a legitimate foothold in the Indian academy on the grounds that it is a genuine science. One reason why this intense debate soon reaches a stalemate is because it cannot be resolved simply by trading words such as 'superstition', 'progress', 'rationality', and 'science' across the gulf that separates the two sides, and this in turn is because the putative referents of these terms are rather mobile. Consider, for example, two subjects : Psychology and Sociology. In the year 1900, very few scientists would have accepted Psychology as a discipline with authentic scientific credentials, and yet in 2005 Psychology has solidly established itself as a science, especially through its branches such as neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, and neurobiology. What about Para- or Trans-Psychology though? Is that a 'science' as well? By 2050, it might become accepted within the scientific canon; as for now, we can only keep our fingers crossed and wait. Now consider Sociology : there are some sociologists who believe that their discipline can be developed into a 'science' very much along the lines of subjects such as physics and mathematics, whereas other sociologists would hotly dispute this move. In other words, what counts as a 'scientific' enterprise is by no means a transparently clear matter even to those within the scientific community. Many of the currently held scientific beliefs (for example, in quantum theory) are extremely counter-intuitive, and history has shown that science has in fact progressed by shattering some of our preconceived 'common-sense' notions.

Does all of this allow us to declare that astrology may become established as scientific at some point in the future? Not quite. This question cannot be answered without grappling with (at least) four fundamental issues. (A) Firstly, as we have seen, we must tackle the thorny question of precisely what counts as a 'science'. What makes physics or chemistry a science? The reliability of its theories? The accuracy of its predictions? The universality of its laws? The empirical verifiability or the falsifiability of its statements? If these are to be regarded as the defining characteristics of a science (and there is much disagreement on these matters), Astrology is arguably not one. (B) This in itself will, however, not rule out Astrology from the Academy for even subjects such as Literature and History do not count as sciences. Consequently, if we wish to claim that Literature and History should be taught in spite of the fact that they are not sciences, we must be able to give adequate reasons as to why Astrology, a non-science, should not be given a place in the Academy.

Should Astrology be taught in Indian universities and, in addition, should this subject earn government patronage when funds for other subjects are (already) scarce? Opinions are sharply divided on this question, and discussions involving it can easily descend into the unsavoury business of exchanging abuses. On the one hand, there are those who armed with the arsenal of Science launch their flaming torches at the dark forces represented by the superstitious and devious practitioners of Astrology. On the other hand, their redoubtable opponents reply that Astrology deserves a legitimate foothold in the Indian academy on the grounds that it is a genuine science. One reason why this intense debate soon reaches a stalemate is because it cannot be resolved simply by trading words such as 'superstition', 'progress', 'rationality', and 'science' across the gulf that separates the two sides, and this in turn is because the putative referents of these terms are rather mobile. Consider, for example, two subjects : Psychology and Sociology. In the year 1900, very few scientists would have accepted Psychology as a discipline with authentic scientific credentials, and yet in 2005 Psychology has solidly established itself as a science, especially through its branches such as neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, and neurobiology. What about Para- or Trans-Psychology though? Is that a 'science' as well? By 2050, it might become accepted within the scientific canon; as for now, we can only keep our fingers crossed and wait. Now consider Sociology : there are some sociologists who believe that their discipline can be developed into a 'science' very much along the lines of subjects such as physics and mathematics, whereas other sociologists would hotly dispute this move. In other words, what counts as a 'scientific' enterprise is by no means a transparently clear matter even to those within the scientific community. Many of the currently held scientific beliefs (for example, in quantum theory) are extremely counter-intuitive, and history has shown that science has in fact progressed by shattering some of our preconceived 'common-sense' notions.

Does all of this allow us to declare that astrology may become established as scientific at some point in the future? Not quite. This question cannot be answered without grappling with (at least) four fundamental issues. (A) Firstly, as we have seen, we must tackle the thorny question of precisely what counts as a 'science'. What makes physics or chemistry a science? The reliability of its theories? The accuracy of its predictions? The universality of its laws? The empirical verifiability or the falsifiability of its statements? If these are to be regarded as the defining characteristics of a science (and there is much disagreement on these matters), Astrology is arguably not one. (B) This in itself will, however, not rule out Astrology from the Academy for even subjects such as Literature and History do not count as sciences. Consequently, if we wish to claim that Literature and History should be taught in spite of the fact that they are not sciences, we must be able to give adequate reasons as to why Astrology, a non-science, should not be given a place in the Academy.

(C) At this stage of the argument, we may introduce the notion of 'causality'. According to most standard forms of astrology, there is some form of a causal connection between celestial movements and terrestrial events and especially incidents in the lives of human beings. One would therefore need to ask what kind of a determinism this world-view implies : is it a 'hard' determinism according to which every event in the future is inexorably fixed, or a 'soft' determinism which would state that the past merely influences the future without preordaining it? If our behavorial tendencies, mental dispositions, and subjective inclinations are governed by astral motions, where shall we 'locate' what we usually call free will, our common belief that our future is, in some way at least, 'up to us'? Are we bound (or 'fated'/'predestined') to become what we do, in fact, become? All of these are passionately contested topics in areas such as genetics, philosophy of mind, and neurophysiology (not to mention feminism, Marxism and cultural theory), and our views regarding the 'scientific' status of Astrology will revolve around our answers to these questions. There are a number of sophisticated view-points to the effect that our 'sense' of free choice is ultimately an illusion, and our acceptance of one of these may make us more receptive towards some version of Astrology. (D) At this stage, the debate will begin to stray into certain areas that come under the umbrella-term of 'History and Philosophy of Science', and instead of studying Astrology we will first have to examine the history of science in ancient India. What kind of traditions did we have in classical India of mathematical inquiry, scientific investigation, philosophical discussion, and logical reasoning? Was Astrology used by these traditions as a means for predicting or forseeing future events?

To summarise, then, whether or not Astrology is a 'science' is not a matter that can be settled by some governmental ukase. This question is only the tip of the iceberg that conceals a host of contentious submerged issues such as how we establish what subjects are to be included in the scientific canon, who polices the boundaries that separate the 'scientific' from the 'non-scientific', and how much of government funds are to be allocated to the different departments across the 'Humanities' and the 'Sciences'. What we lack in India today is a widely-shared common framework within which questions of this nature can be raised, debated and responded to by people from different educational backgrounds, but unless we are able to initiate some discussion on these, the ponderous matter of whether or not Astrology is a science will remain quite untouched.

To summarise, then, whether or not Astrology is a 'science' is not a matter that can be settled by some governmental ukase. This question is only the tip of the iceberg that conceals a host of contentious submerged issues such as how we establish what subjects are to be included in the scientific canon, who polices the boundaries that separate the 'scientific' from the 'non-scientific', and how much of government funds are to be allocated to the different departments across the 'Humanities' and the 'Sciences'. What we lack in India today is a widely-shared common framework within which questions of this nature can be raised, debated and responded to by people from different educational backgrounds, but unless we are able to initiate some discussion on these, the ponderous matter of whether or not Astrology is a science will remain quite untouched.

Sunday, February 27, 2005

The Curious Case Of The Indian Memsahib

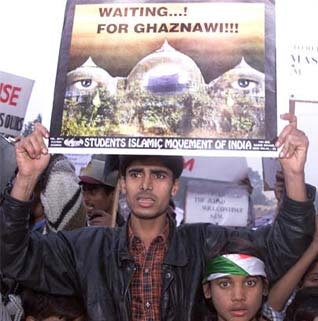

I have always been intrigued by the role of the Memsahib in India's colonial history, especially given the fact that quite a few of them, to use the anthropological jargon, actually 'went native', and acted as a counter-hegemonic column against the Empire. Think, for example, of Madeleine Slade, daughter of an English Admiral, who became Gandhi's follower; the Irish lady Margaret Noble who became a devoted disciple of Swami Vivekananda; and Annie Besant who even became president of the Indian National Congress in 1917. The British Memsahib was in a highly ambivalent position, for she was both empowered from one perspective and disempowered from another. With respect to the natives, she enjoyed a superior position in her status as an European, but in relation to her husband she was still within a patriarchal Victorian system and was consequently in an inferior social rank within inner British circles. Thus the Memsahib lived at the intersection of two very different forces threatening to pull her apart in two opposite directions : in her private life, she had to submit to her patriarchal husband, but in the public sphere, she exercised power over the colonised natives. Hence the efforts of the Indian Sahib to police the Memsahib's activities in order to ensure that she would not actually fraternise with the enemy, thereby colluding with the dark and sinister 'Oriental' forces that were embodied in the native.

(It is interesting to note that these ambiguities are reproduced in post-Independence India in the ominous figure of the mother-in-law who has replaced the Memsahib : with respect to her daughter-in-law she wields a great degree of authority, but her own sinister powers are circumscribed by the yet higher authority of her husband.)

Why Has Everyone Become A Poet?

Allow me the ironic licence of putting the matter somewhat provocatively : the reason why we have all become poets today is because we are afraid of negotiating the intractable territories of history, and instead turn to Poetry as our last line of defence from behind which we nervously peer at the estranged world outside us with a bemused and somewhat perplexed curiosity. Now that we have debarred ourselves from using outlawed terms such as 'judgement', 'truth', 'meaning', and 'objectivity', and have forced ourselves to become de-centred and dis-continuous subjects, we are compelled to run away from the realm of history and console ourselves with endlessly playing with our slipping and sliding words that must be perennially deferred. Consequently, Poetry is no longer about the real world 'out there' (for we have declared at the last Party meeting that there can be no such entity) and has degenerated into a sophisticated form of narcissism to amuse ourselves and an anodyne activity to fill in our unbearable moments of ennui.

Allow me the ironic licence of putting the matter somewhat provocatively : the reason why we have all become poets today is because we are afraid of negotiating the intractable territories of history, and instead turn to Poetry as our last line of defence from behind which we nervously peer at the estranged world outside us with a bemused and somewhat perplexed curiosity. Now that we have debarred ourselves from using outlawed terms such as 'judgement', 'truth', 'meaning', and 'objectivity', and have forced ourselves to become de-centred and dis-continuous subjects, we are compelled to run away from the realm of history and console ourselves with endlessly playing with our slipping and sliding words that must be perennially deferred. Consequently, Poetry is no longer about the real world 'out there' (for we have declared at the last Party meeting that there can be no such entity) and has degenerated into a sophisticated form of narcissism to amuse ourselves and an anodyne activity to fill in our unbearable moments of ennui.

Poetry intervenes at such a critical moment to redeem us : in the rarified atmosphere of Poetry we find ourselves blessed with a consecrated medium through which we can 'bracket out' the troublesome external world as an unnecessary irritant and discard it to the dustheap of history. Through Poetry, we can give vent to our modish suspicion of all belief-systems or patterns of political praxes that claim to analyse and transform the social structures within which we are all implicated. Instead, Poetry becomes a way of affirming our apotheosis of spontaneity, fluidity, arbitrariness, vacuity, and depthlessness, and of expressing our vitriolic denunciation of any attempt to discover a stable reality that may underlie these playful activities.

In other words, under the hallowed aegis of Poetry, we can retreat into ourselves with consciences free from guilt, and take shelter in a domain from which nothing can dislodge us or ruffle us in our placid equanimity as we ceaselessly pour out word after word after word after word in listless chains of meaninglessness. We have all become poets today but our Poetry is formally empty; it speaks no longer of the blood and the sweat of those who labour under the sun in the heat and the dust so that we, the privileged miniscule few, may have the time and the leisure to pour out our poesies in a never-ending stream; it cannot even say anything meaningful to those who really need it; it has become but an extension of our pastoral tea-party game of dissolving the world and it ultimately dissolves itself in the process; it is our feckless justification of our 'individuality', our final enclave of uniqueness against the anynomous hordes of the uncouth barbarians out there; and yet it flounders helplessly in the face of the chaotic reality of history from which it becomes progressively more and more disengaged every passing day.

Thus with the help of Poetry we run away from the harshness and the savageries of history into the impenetrable citadel of the 'I', and naively pretend that there will be less starvation, hunger, ethnic conflict, patriarchal oppression, and colonialism if only we could make better and more civilised human beings out of ourselves simply by taking a crash-course in how to write Poetry, how to analyse the poems of an eighteenth-century sonnetist, or how to swim along with the logorrhoea of a contemporary Master. In this manner, Poetry has become the supreme anaesthetic for the imperturbable minds and hearts of an entire generation for whom Poetry is merely a stylish mode of celebrating one's originality or one's ingenuity in coining neologisms that will be forgotten, in any case, after two weeks. Consequently, our Poetry has nothing to say about the brute realities of gender discrimination, wage inequalities, multinational capitalism, racism, genocide, and neo-imperialism, for we have allowed ourselves to be comforted by the illusion that Poetry dwells in some timeless ethereal zone above the earth, occasionally landing on it but never quite staying on long enough to suffer with the voiceless, the speechless, and the nameless.

Thus Poetry, having lost the tenacity to challenge the oppressiveness of the socio-political contexts within which we live, has instead become a symptom of our failure of nerve in the midst of the ambiguities, the complexities, and the conflicts of history, and a mute reminder of our obsessive preoccupation with our words, and ultimately with ourselves.