In Search of 'Objectivity'

Whether or not they are themselves 'scientists', most people believe that what distinguishes the activity that goes by the name 'science' from other products of human imagination, ingenuity, creativity, and industry is that the former is 'objective', and thereby gives us Objective Knowledge. What, however, does it mean to say that science is 'objective'?

(A) Firstly, science is an enterprise that is carried out by a certain group of people, whom we call scientists, such that these scientists are in active communication with one another. Perhaps they meet one another occasionally at conferences, or read about one another's hypotheses in international scientific journals, or have access (through a library, the Internet, and such sources) to a vast body of calculations, predictions, theories, conjectures and refutations that has accumulated over the centuries.

(B) Secondly, the messages that are passed among scientists in this manner are consensible, by which I mean that these messages are written in a language which can be understood universally. The favoured language is, of course, that of mathematics through which the contents of these messages can be readily transferred from, say, the University of Canberra in Australia to the University of Calgary in Canada as unambiguously as possible. As Galileo used to say, 'Nature is written in mathematical language'.

(C) Thirdly, the aim of the transferrence of these message is the attainment of the maximal degree of consensus among scientists. This does not mean, in most cases, that all competent scientists will come to accept the proposed theory but that a large majority of the scientific community will do so. These other scientists should be able to reproduce the results or events proposed by these theories through the design of certain experiments carried out under controlled conditions ('within the limits of experimental error'). In this process, through the countless repetitions of experiments or the criticism of the theory on which they are based, errors can be eliminated or the theory itself rejected.

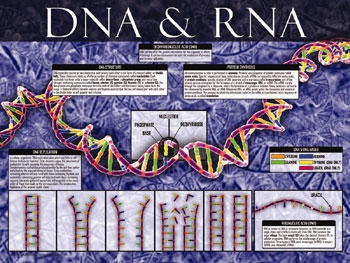

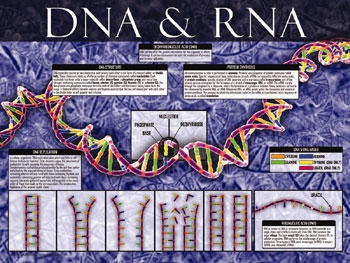

(D) From the above, we see that the objectivity of science should rather be regarded as intersubjectivity. The reason for this is that no individual scientist can possibly repeat every single experiment that has been proposed in the scientific literature, but has to rely on the good judgement and the scientific competence of her peers and her fellow-scientists. In this era of hyperspecialisation, a scientist investigating the structure of DNA would, in all probability, never come around to finding the time or acquiring the comptetence to design experiments to test Einstein's Special theory of Relativity, but she can trust that other scientists have, under strict conditions of mutual criticism, tested this theory. (And the same applies for a quantum cosmologist who accepts scientific discoveries in the domain of micro-biology, a field she may have neither the time nor the inclination to venture into.)

(E) Through this process of intersubjectivity, a map or a picture of inter-related and coherent theories is built up, and this map is called a paradigm. However, the development of this paradigm is not a guarantee that 'the Truth' has been attained, once and for all by the scientific community, for history has shown us that these paradigms themselves have a history of their own. Once again, science is not so much an objective as an intersubjective enterprise into which all scientists who share the same paradigm enter. To become a scientist one has to first accept certain statements that she is not in a position to immediately test or verify without further training : for example, within the Newtonian paradigm, one must first accept the validity of Netwon's three laws of motion, and the same applies for other paradigms in the fields of microbiology, cosmology, relativity theory and so on. In this process, however, a scientist may imbibe these foundational statements so completely that they become her 'second skin', and consequently, she may not be able to easily accept theories or predictions that are in variance with such statements.

(F) Therefore, we must give up the illusion that scientists are 'neutral and dispassionate' observers. The grain of truth in that phrase is that the scientific community is indeed governed by the most stringent rules concerning the criticism of one another's theories, and the regular and careful repetition of designed experiments. However, the scientist cannot be 'neutral' as to which paradigm she wishes to live in : she is already born into one, and has no, as we say, choice in the matter. To be sure, after much training she can begin to offer reasons as to why the paradigm that she inhabits is 'better' than or 'superior' to other discarded ones, but she is not entitled the perfect confidence that her paradigm is the final and absolutely one. For example, someone born in 1994 cannot choose to reject the Neo-Darwinian paradigm that is currently regnant in evolutionary theory, and has to live, move and exist within this paradigm, and this in spite of knowing that it may come to be replaced by another paradigm in say another fifty years.

(G) It is because every paradigm is a set of inter-connected views that it is extremely difficult to design one Crucial Experiment that will falsify an entire paradigm. (The Michelson-Morley experiment to prove the non/existence of the ether is a rare example of such a Crucial Experiment.) Most paradigms have a set of 'core beliefs' surrounded by a periphery of 'auxiliary beliefs', such that even if a few of the latter are given up the former can stand untouched. Therefore, even if certain random observations seem to contradict a paradigm, it is possible to incorporate even these into its conceptual structure by making appropriate changes in or sometimes even by dropping some of the auxiliary beliefs. However, during certain 'periods of scientific crisis' the number of auxiliary beliefs that has to be dropped may become so large that significant changes may have to be introduced into the set of core beliefs : in such process, a new paradigm emerges out of the former (such as the Newtonian-mechanical paradigm from the Aristotelian-cosmological around the 1700s, and the quantum-mechanical from the classical-mechanical around the 1920s).

In short then every paradigm is a conceptual web, mesh, or network of inter-related statements, and scientists belonging to a certain paradigm form a group of communicating enquirers who, on the basis of such statements, press onwards to explore the world which is seen in the light of this paradigm. Science, in other words, is neither, strictly speaking, a subjective nor an objective affair, but an ongoing process in which messages, coded in a universally understood mathematical language, incessantly flow into archives where they can be preserved, read, assimilated, understood, criticised, (sometimes) verified and (sometimes) falsified by the community of competent scientists which is forever recruiting and training novices.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home