The Prayers Of Two Atheists

On Good Friday today, I cannot help remembering a most remarkable experience that I had in Cambridge within a few months of my arrival here from Delhi seven years ago in the white winter of 1998. I was then, and I perhaps am even today, a 'confused believer', meaning by that phrase a person who does not, on the one hand, deny the existence of God but who, on the other hand, fails to understand why a transcendent God, perfectly blissful in God-self, should have wanted to create a precarious world of fragile beings who are forever steeped in so much abject misery. These mortal questions were put to me most pointedly one cold November evening in 1998 when I went to a graveyard situated seven miles from my college, Trinity. As I was walking through the narrow rows of speechless gravestones, trying not to step on the autumn branches that were strewn all over the moist earth, I saw a middle-aged woman wearing a shining black coat kneeling at one of the gravestones, and softly murmuring something to herself. I stopped in my steps and was trying to read the epitaph over her shoulder when she suddenly turned round, stared at me for a frozen moment and, while still kneeling, burst out crying.

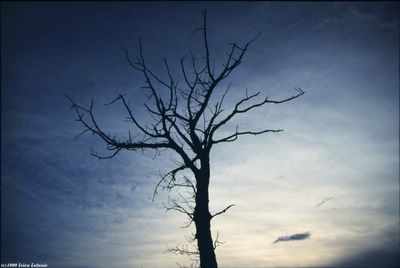

Almost at once, however, she restrained herself and fell silent. With her, so did the black crows on the leafless branches above, and a most dreadful silence began to fill the cold distance between us.

'I hope you will excuse me', she said at last breaking the uneasy calm, 'For a moment I thought you were him. You do bear a striking resemblance to him, and I felt that he had come to pay me a visit today.' And that was how she started narrating to me some isolated fragments of a heart-stirring story.

She, Fiona McGrath, had been born sometime in the 1950s in the poverty-stricken highlands of Scotland, though she could remember neither of her parents. She had been adopted by a man, Mark Witherington, who had taken her under his wings from an orphanage in the outskirts of Inverness and who now lay buried in front of her. It was in his home in Cambridge that she had spent most of her childhood and teenage years, and his home was the place around which some of her fondest memories were centred. He had lived mostly by himself, devoting all his spare time away from his work to being with her. Three weeks before he died on Good Friday, 1982, he had told her that his entire life had been one relentless protest against God for having created this world, this vale of suffering, and that the true atheist was not the person who denied God's existence but the one who did not repeat God's mistake of creating this world by bringing babies into this world. It was for this reason, he explained, that he had never desired any children of his own, but had adopted her with the hope that he might be able to remove a little bit of suffering from this world.

As for Fiona herself, she was an atheist in the spirit of her father. She would come to the graveyard every year on Good Friday and pray. But pray to whom or to what? She simply did not know. She would kneel down at his gravestone, drink in the surrounding silence, and strengthen her resolve to carry on through her own life the long protest that her father had sustained against the faceless, the nameless, the heartless, and, above all, the pointless God.

Last year, I went to that graveyard again on a summer evening, and when I went to the familiar spot close to the dilapidated brick walls, I saw a new gravestone beside the old one, that of Fiona McGrath's. Beyond their gravestones, the red sun was slowly going down into the misty fields where three black cows were quietly grazing, unware of the devious ways of gods and human beings. And high above them, there were two stars shining at each other in the dusk sky, stars that were scrupulously guarding the graves of two atheists and were patiently passing on their unspeakable prayers to a speechless God.

10 Comments:

At 27.3.05, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

"the true atheist was not the person who denied God's existence but the one who did not repeat God's mistake of creating this world by bringing babies into this world"

Not the first time this has popped up on this blog. But there is a big loophole: it neglects a very important fact - the fact that we humans (athiests or not) do not know what happens before the new baby and after the dead man. On what grounds can we suppose that annihilating all traces of God's current mistake (by not bringing more babies into the world)we are not giving him a chance to commit a more gruesome mistake? What is the assurity that his sadist tendencies will not manifest themselves with greater force in another mistake? Maybe we need to figure out another, more foolproof, way out within the current scenario of things - after all the same mistake which allows for so much suffering also encompasses a universal incination to remove it.

At 27.3.05, The Transparent Ironist said…

The Transparent Ironist said…

You are very correct in saying that I do not know what shall happen to me after I am dead. It could turn out that the infinite God is also infinitely resourceful in His sadism, in which case I cannot thwart His grand designs of malevolence in any way. While wishing to find out with you 'another, more foolproof way out within the current scenario' (to use your words), I would not wish to create, in the meantime, the potentiality for yet more suffering in this world by bringing babies into it. It is a sort of permanently deferred moratorium. This is not, needless to say, a totalitarian diktaat that nobody can have babies : I speak only for myself here, celebrating our contemporary mode of 'individual distinctiveness'.

At 27.3.05, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

A permanently deferred moratorium - that is a good one :)!

Your intention might not be to turn it into a totalitarian diktaat, but this argument does have the potential to become one especially if we ignore our ignorance of not only what happens to us after we die but also WHAT WAS HAPPENING TO US BEFORE WE WERE BORN. Having said that however, I must confess that I myself do not see much point in having babies especially given the fact that there already exist thousands of them who would appreciate a human guardian.

At 28.3.05, The Transparent Ironist said…

The Transparent Ironist said…

WHAT WAS HAPPENING TO US BEFORE WE WERE BORN : I am not sure if I understand what that statement means. Are you trying to say that 'we' are essentially disembodied selves that uneasily hover over the surface of the earth until the moment of our earthly births when 'we' descend into physical bodies where 'we' become incarnated? Otherwise, one could simply say that before 'we' are born there is no 'we', and that this is all there is to say on this matter.

At 29.3.05, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

Even I am not sure what that statement exactly means and that is what I am trying to say.

At 30.3.05, The Transparent Ironist said…

The Transparent Ironist said…

If you are not sure of what that statement means, what has happened to the 'loophole' with which we started this line of conversation? It would seem that the loophole has disappeared into itself. No?

At 31.3.05, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

By not knowing what that statement means I mean empahsise the NOT KNOWING part and not the STATEMENT part and the loophole lies in the former.When you ask me what I exactly mean by 'what was happening to us before we were born', I am sure you understand the semantic meaning of the statement but beyond that I confess my ignorance - if I knew what it meant then there would be no point in asking the question (and of this whole conversation). I cannot tell you something I don't know. Yes you may be right in saying there is no 'us' before we are born and then a more apt version of the question would be 'what was happening before we were born'. But either way the POINT is that we cannot even be sure of what is the more apt version because WE DO NOT KNOW (Loophole! Loophole!).

Maybe you can shed more light on this issue by explaining what you mean by 'I do not know what shall happen to me after I am dead'

At 31.3.05, The Transparent Ironist said…

The Transparent Ironist said…

I do not know what shall happen to me after I am dead : This is my way of saying that I do not know if there is a state of post-mortem existence.

At 31.3.05, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

You got it!

At 31.3.05, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

Likewise for pre-mortem existence

Post a Comment

<< Home